Arthur Sharp remembers traveling with his elders in search of a new area to call home after a devastating earthquake rattled Southcentral Alaska in 1964.

“They came over and looked around, and I was with the elders,” Sharp, a 57-year-old Alaska Native, recalled. “They all agreed that this spot here would be the ideal place to make our village. One by one, each household that lived in Togiak moved to Twin Hills.”

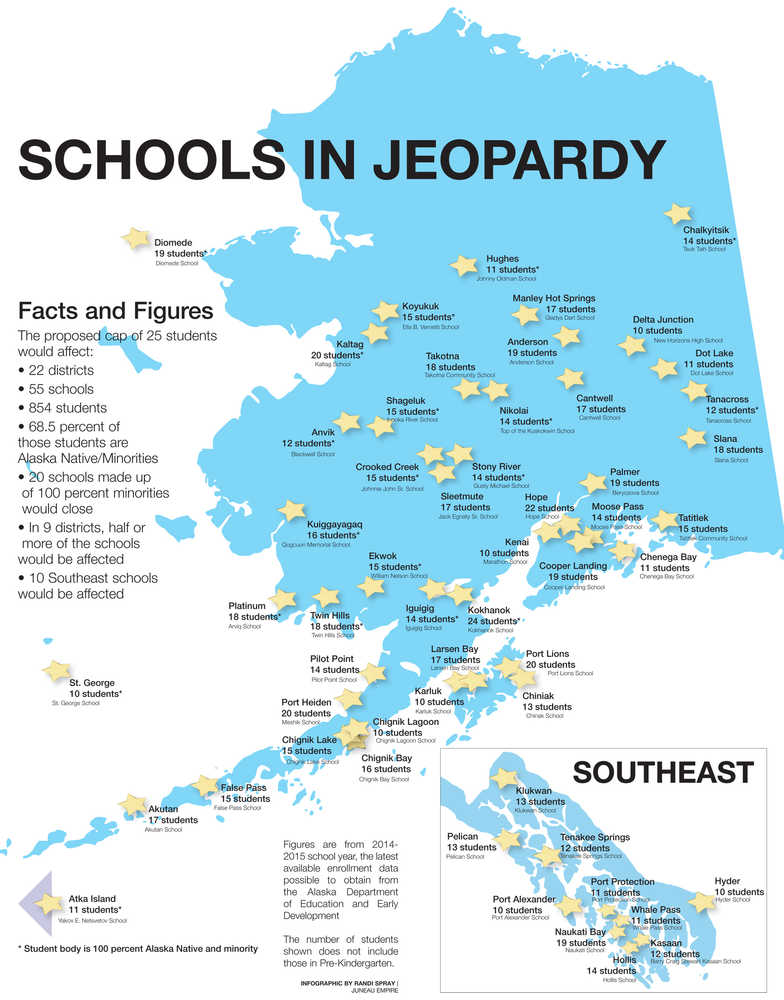

When Sharp talks about his village, which sits 65 miles east of Dillingham as the crow flies, he mentions safe high grounds, the abundant moose and the four kinds of salmon that visit each year. Despite this deep history and love, he and his wife would leave it all behind if the school where their 8-year-old son Daniel attends is closed. It’s the only school in the village, but if the Alaska Legislature changes the parameters for school funding, it could be among 55 schools that disappear.

The State of Alaska provides a base amount of funding for schools with an enrollment of at least 10. Last year, 19 students were enrolled at Twin Hills School, a number that keeps the school in the safe zone for operating costs. A school with an enrollment number less than 10 is funded on a per-student basis, and operating costs must be supplemented by the community.

The reality is anything less than 10 students becomes too great a financial burden to operate. Tenakee Springs in the Chatham School District, just 50 miles southwest of Juneau, temporarily closed in 2014. The only school in Pelican faced a similar shutdown threat in 2013 when enrollment dropped to seven students.

More than a dozen schools any given year are just one student above that critical funding cut-off. Whispers from the capital have some school officials and parents up in arms. Many are worried the bar could be radically moved, as far as rural schools are concerned, and put those with less than 25 students in jeopardy.

The impact of such a change would be felt by 55 schools in 22 districts, with a combined student body of 850. Of those 850 students, about 68.5 percent are Alaska Native or another minority. In 20 schools, the entire student population is Alaska Native.

‘Only so much funding’

“I know that they’re scared, ultimately the underlying fear is ‘What’s going to happen to an opportunity for my kid,” Rep. Lynn Gattis, R-Wasilla, said.

However, a statewide budget deficit close to $4 billion due to slumping oil prices means looking for savings in every area, and Gattis said all she is asking of people right now is to not be afraid of having a conversation. She did not confirm she was going to propose a bill to change the student minimum, that’s something she said will depend heavily on what she sees in the new budget, due from Gov. Bill Walker by Dec. 15.

Gattis also said a change this big shouldn’t be mandated from on high without consulting those it would most greatly affect, but all parties have to be willing to sit at the table and have the discussion in order to avoid a mandate-like situation.

“There’s only so much funding,” Gattis said. “We all need to make compromises.”

Sen. Mike Dunleavy, R-Wasilla, is another name superintendents around the state have associated with the possible student minimum change. As the education chairman, he said he does not know of any definite plans to draft a bill that could result in school closures. However, he echoed Gattis’ sentiment that everything must remain on the table during savings discussions.

“I believe word (about changing the minimum) came from me talking with some folks at ASA (the Alaska Superintendents Association),” Dunleavy said. “It was just a conversation … but it’s the largest part of the budget. It would not shock me if somebody did introduce a bill. Nothing’s going to shock me.”

How the senator would vote on such a bill depends on the type of savings it could actually create for the state, Dunleavy said. He said it would have to be significant enough to outweigh the effects sure to be felt by the rural communities that live and die by their ability to attract families to the area with the promise of a school.

Elizabeth Nudelman, the finance director for the Alaska Department of Education and Early Development, said immediate savings would total roughly $5.9 million if only the average daily membership (ADM) requirement shifted to 25 students and everything else stayed the same. Nudelman said she couldn’t yet have a full conversation about savings because nobody has asked her to run figures based on specific changes. Her calculation is based on a cut-and-dry formula that doesn’t account for the possibility of schools, and in some instances entire districts, shutting down.

“Does such a move at any threshold create such a savings that it would be worth the impact?” Dunleavy asked. “I’m acutely aware of the issues out there of a school closing on a community. It devastates a community, there’s not doubt about that.”

That reality, however, is not enough to shut down the conversation. Dunleavy said if people stop talking about changes to education policies because they’re afraid of the effects, next is a halt on changes to road projects or other community endeavors. Soon, no one is talking about anything, Dunleavy said.

Gattis echoed Dunleavy’s concern, adding that stopping the conversation can be an assault on progress.

“If we’re afraid to look at this as an option and we shut down the conversation, then we’re not asking how we could make things even better,” Gattis said. She too attended a small school that no longer operates in the rural village of Gulkana, and said she can see the upside to alternatives such as virtual schools, weekly boarding schools or consolidated schools that give students more interactions and experiences they might currently lack.

“Could we do a better job? That’s what I’m asking,” Gattis said.

Early defense

Back in the village of Twin Hills, where 8-year-old Michael Sharp goes to school, teacher Meghan Redmond is leading a charge of several small school teachers and administrators who don’t think the conversation is worth having. Telling families they have a choice if a school shuts down — moving to larger areas, virtual or correspondence education and home school — isn’t much of a choice at all, Redmond said.

“They shouldn’t be forced to move away,” she said. “That should be a family’s choice. They can choose to do that if they don’t like what our school can provide, but we try to give students the same opportunities they could have anywhere.”

Redmond said difficult economic times have always meant watching out for budget cuts that could hurt schools, but it wasn’t until she read an article in the Empire in early October that she realized things could actually be in motion and her job — and her students’ classroom — could be on the line.

To create a support network for other small schools worried about changes to ADM, she started a social media hashtag (#smallschoolsmatter) to shift the conversation to the lives it could affect. Schools and students from around the state are encouraged to join the online conversation and send photos of their classrooms, putting faces to the small enrollment numbers.

The Twin Hills community, along with other Alaska schools, started letter writing campaigns to the governor asking him to remember these small schools in the event that someone introduces a bill to change the ADM.

It’s a lot of work, preemptive work at that, but Redmond said the level of early defense seen across the state is a message in and of itself.

“It’s that important to us,” Redmond said. “It’s so important to us that we don’t want it to become a bill.”

Also on their way to the capital along with letters from children are resolutions from various groups asserting the ADM should not change. Those groups so far include the Alaska Superintendents Association, the Association of Alaska School Boards, the Twin Hills Village Council, the First Alaskans Institute Elders and Youth Conference and individual resolutions by districts across the state.

Legislative defense

Despite what Gattis and Dunleavy said about the rumored changes being just that, rumors, legislators from both sides of the party line are also proactively taking a stand against the change.

Sen. Gary Stevens, R-Kodiak; Sen. Lyman Hoffman, D-Bethel; Rep. Bryce Edgmon, D-Dillingham; and Rep. Bob Herron, D-Bethel, penned an op-ed to the Alaska Dispatch News titled, “If we cut Alaska rural schools we’ll lose so much for so little saved.” The letter declared all four legislators against changes proposed by “Railbelt legislators” to alter the ADM.

Stevens said his participation in the letter isn’t a sign he won’t consider talking about savings in different departments, but this won’t be one he’ll be in favor of.

“My main concern is those kid are going away, we still have a constitutional responsibility to educate them,” Stevens said. “The options I‘ve heard so far are just really not adequate.”

The minimal gain from such a large loss is also a concern, Stevens said. His experience as a superintendent in Kodiak where schools have at times fallen below the current ADM requirement have shown him first hand the struggle to keep a school operating when full funding isn’t an option. Funding has to be supplemented from somewhere else in a district or the community’s budget.

It’s that kind of supplementation that Gattis said paints the other side of the savings coin. It isn’t just money from the Department of Education and Early Development that is part of a district’s budget, it’s augmented by community monies that could be saved as well, she said.

A disproportionate affect

“It would be difficult to show there is positive savings and I think it would very easy to show the detrimental impact,” Rep. Sam Kito III, D-Juneau, said.

Kito, whose district could loose funding for schools in the Chatham Schools District if ADM changes were made, said the conversation alone isn’t worth having because smaller communities could interpret such talks as decreased support for them in favor of larger areas.

In the end, Kito said he would definitely not support any such bill if it came across his desk.

“I think if you’re talking about raising that standard then, in my opinion, you’re also talking about making those communities unviable, which means you’re talking about closing down communities,” Kito said. “We want to find a way to support everyone in Alaska.”

In Redmond’s classrooms — she teaches students from the third to eighth grade — a loss of that state support would not only be a blow to the community, Redmond said, but a disproportionate blow to Alaska Natives.

Redmond’s school is one of the 20 in Alaska with a 100 percent Alaska Native student body.

Arthur Sharp of Twin Hills said as a child he saw the effects of schools once managed by the Bureau of Indian Education and then transferred to the state; it’s a system that doesn’t always consider the authority of elders and cultural policies. He didn’t like it then, and what he likes even less is what he worries could be the state bailing on a deal he never wanted them to be part of in the first place.

“They’re not just targeting education,” Sharp said. “It’s everything that benefits a minority.”

• Contact reporter Paula Ann Solis at 523-2272 or at paula.solis@juneauempire.com.