By Marina Anderson

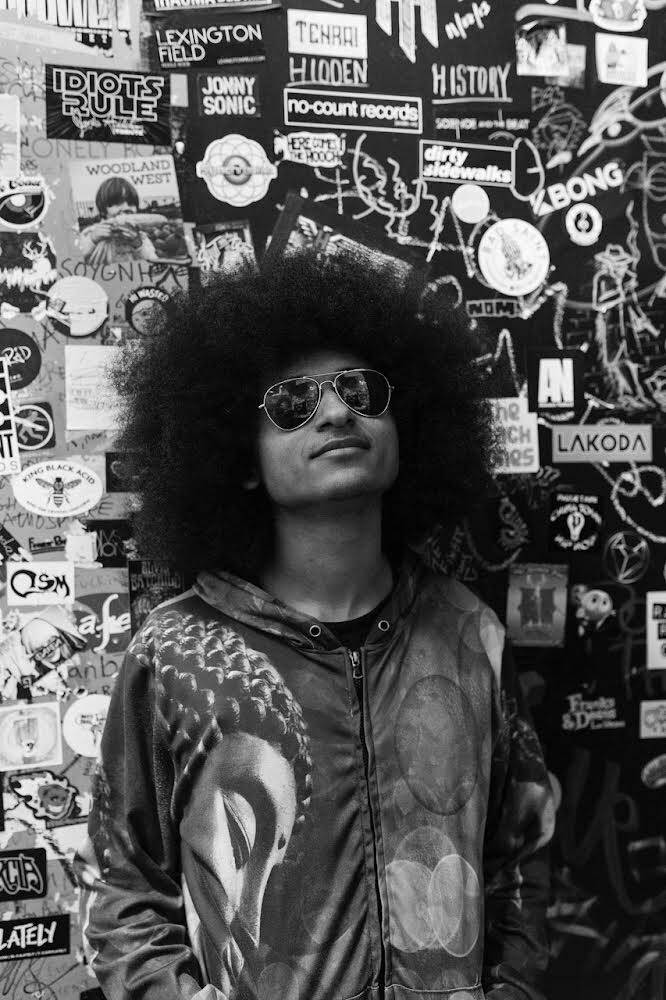

Arias Hoyle’s voice is so smooth it could put you in a trance. Hoyle, whose stage name is Air Jazz, is a 20-year-old Afro-Indigenous musician from Juneau celebrated for his place-based rhymes. In 2021, he helped orchestrate the inaugural Rock Aak’w Fest which was among the first Indigenous-focused music festivals in the nation.

Held in Juneau with 30 artists and streamed digitally to countless transfixed listeners across the nation, Rock Aak’w reached the ears of self-proclaimed “fangirl”’ Marina Anderson on Prince of Wales. Anderson, who is of Haida, Tlingit and Jewish descent is an activist and advocate for contemporary fusions of Indigenous expression.

For this month’s Resilient Peoples & Place column, and in honor of Black History Month, Anderson and Hoyle discuss art and Hoyle’s experiences at the intersection of Black and Indigenous identity. They talk about reclaiming the Tlingit Language, the ‘new wave’ of Indigenous art forms, and the power of rap and storytelling for healing communities and generating joy.

MA: Arias, tell us a little about yourself, your upbringing, what makes you tick?

AH: I was originally born in Anchorage, Alaska, but I’ve spent my whole life in Juneau with my adoptive family and they’re genius, they’re great people. Growing up, I was listening to a lot of my family make music actually. For example, both my older brothers are hip-hop producers and my dad is a singer -songwriter who plays guitar. And even though he mostly keeps to himself locally, he really influenced me to become a performer on stage and do what I do.

I officially started writing and recording music in middle school. At 14, I went to my first recording studio with my friend Justin Miller in Juneau, and the rest has been history.

I just love making music— It’s my vibe and it’s the art that reps these people- our family, our ancestors- that we come from.

MA: Yes, I understand that. I feel like everything we do for expression as Indigenous people marks time in our collective history. And 100 years from now, when people listen to your songs, or pick up those earrings that a beader made, it’s all indicators of where we are today.

AH: Yes, that’s powerful. It’s a timeline and that keeps going to this day.

MA: And I think it’s really important that we define that history for ourselves.

Speaking of ancestry, your lineage is so rich, tell us about being Afro-Indigenous and how your racial and cultural identities coalesce in your music.

This journey really began when I was 16 and I did the first music video for Tlingit and Haida, Ix̱six̱án, Ax̱ Ḵwáan (I Love You My People) because it was at that moment that I realized that I can combine my African American lineage with my Tlingit lineage into one. So I really found my racial identity, and not just my racial identity, but my identity period and I think that manifests through the songs.

MA: That’s so strong, that first song resonated with so many of us. I remember sitting at President Peterson’s house and there were probably 30 of us there watching it on repeat, getting so excited by it. Just seeing our language and our culture, fresh and alive and adapting at the hands of our youth- was so powerful. It was out of the textbook, away from our close circles in Culture Camps and our villages and into a rap on the internet for everyone to see and to celebrate.

And it was kind of saying, ‘we’re not going to be oppressed anymore’.

AH: Yes, and all our ancestors, all our grandmothers are in us creating this ‘new wave’ of contemporary music as we go from oppression to expression.

We look at so many examples right now. You know, we have the Halluci-nation, we have our boujee natives with the Snotty Nose Rez Kids, we got “Reservation Dogs” and Quannah Rose is incredible and there’s just a long list of artistic people that are from this region too and they’re just so expressive about it and I even love the word boujee because that really does express just how dope and how worthwhile it is to flex your heritage.

MA: When that song came out, I was like, we’re not that boujee and then I was looking around and noticed that I did have five rings on my fingers. I have earrings on no matter what, even if I’m going out fishing or whatever, I’ll drop everything and grab them. I have emergency earrings in my car.

With regards to celebrating the language in songs, I used to be almost jealous about how other people, even you, are more fluent in our Indigenous languages. Now, I’m rooting for everybody, and with some of your songs even when I don’t know all of the words you are saying, I understand what you are saying and it’s really empowering me.

What role has this art and this language played in your growth?

AH: It’s played a huge role for me. I think part of my personal growth comes from this whole movement, that collective growth you described. Having this entire community you come from and knowing that as soon as one person makes that one song, or tells that one story, or does that one dance with their dance group, it gets noticed and acknowledged by all of your loving family and it just builds upon it like that.

This person inspires this person over here to become a fluent speaker, and then this fluent speaker helps this young artist make songs in their native tongue and then that young artist can go on to inspire many.

You have local Indigenous people who have been on American Ninja Warrior, another who has illustrated an Elizabeth Peratrovich mural, another who got her on Google, and then we have people like you, Marina, who really bridge the generations together and really make us beloved and peaceful about ourselves. So I think it’s really important. If we want to make it as artists to embrace that collective progress, to be thankful for it and share it with everyone around.

MA: I feel like it was a fight to find Indigenous music for so long and now I feel like there’s this whole scene.

With Rock Aak’w Fest, I was just glued to it. It was important and it wasn’t just our music it was about celebrating that Indigenous excellence from all around the world and it was really beautiful. I know you were part of starting that, why do you think it was so impactful and well received?

AH: I think one huge reason is we’re in this pandemic era, where it’s been so hard to be together and to do just about anything. Simultaneously, we’re asking ‘what is it that our Indigenous people can do to help?’ And that’s a reawakening of our art, pushing it even further and bringing people together both from inside and outside of Alaska. Then the local musicians, who showed up with all this amazing skill and prowess that they’ve been working at, for well over a decade now– longer than I’ve been even starting music. So it really was the place to be and it’s going to be that place every year that it comes up. Next show will be in 2023, mark your calendar.

MA: Okay, let’s talk more about your actual music. For people who haven’t had a chance to tune in yet, what do you rap about?

AH: Yes, so my messages vary from time to time, though the primary subject matter that I choose from is spirituality, reason, purpose, and overall positivity. Even if I bring up topics that aren’t so fun and are a bit more serious, I want to do it in a way that sounds like a solution and a positive outlook.

MA: Could you give us some examples of tough themes you approach through music?

AH: I have a song called Tranquility, where the main theme I revolve around is essentially the afterlife. Not focusing on whether you believe in it, or what it looks like, but just knowing that you can have a peaceful life and a peaceful exit.

The hook goes:

I’ma say, namaste.

My mistake, do not resuscitate.

‘cause I don’t want to stay.

And that means I’ve lived a full life and all is going good, and I’m easy on the way out too. And yeah, so that’s an example where even if a topic is a little bit serious, you can make it easy, make it slick. Because it’s more relatable.

MA: Do you have another string of lyrics, you are most proud of, you want to share?

I’d say my most passionate lyrics are the ones I wrote for my song ‘Mirrors Edge’ which is off of my last LP. ‘Last Chance Chilkat’ and it’s one of my more introspective songs.

It goes:

I’m not into wishin’

It’s my intuition to keep spittin’

Continue your mission, until the real ones give you a listen.

It’s your vision, no Hindu Christian, this your own religion.

Your brain is in chains like you’ve been to prison.

And what that stanza means is that you’re in your own mind. You have your own purpose. No one else can do it for you. And it is your job to look within yourself and make something happen. I think that applies to a lot of visionaries out there. Other songs I’d want people to check out would be “Life in a Foster’s Home,” “Dream Catcher,” and “Tranquility.”

MA: That’s pretty powerful. So one lyric that always sticks out to me is when you talk about smoking a half pound of salmon. It cracks me up. And what do you think is so significant about singing about something like that?

AH: If we were to look at a lot of the lifestyle of Indigenous people of Alaska, you’ll hear familiar topics like the salmon, the fry bread, the beadwork, and I think it’s fun to take those ways of life and make it a little clever, make it a little humorous and fun for everybody.

Because that’s a good way to introduce new people to your people—Give them a good chuckle. Give them a good one liner, let them ease their way in, they’ll be like, ‘Oh, look at these guys. They smoked salmon over here like, pass me the salmon. I want to smoke some too.’ It’s fun, and it’s creating introductions.

MA: Another one of your songs that really hit me and that I make all of my nieces and nephews listen to before they get their licenses, is your song about not drinking and driving. What’s the story of this song and what’s the power of approaching such a difficult topic with music?

AH: I really do appreciate that this was the message of mine that you were spreading to younger ones because I love when a PSA is done the right way and it actually reaches our young relatives and whoever else needs to hear it.

Yeah, so when I made that song, I was marinating with it a bit. The main thing I thought about was with the amount of songs I’ve done that are more on the fly and an easy introduction to our people, It would be important to have that track as contrast that shows that it’s not always peaches and cream for the people we come from. This song keeps it real and it doesn’t sugarcoat.

When you meet our relatives on the bloodline, they have likely experienced these kinds of traumas. This music is used as a kind of healing moment. It’s a moment of healing so that you’re like, “Okay, I see you guys really do have your own struggles and demons like we’ve had, and you want to have that be heard in a way that was taken seriously.

The art and the music is the medium to use for messages and PSAs because if there’s one thing everyone has in common, it’s that everyone has a taste in music. Everyone is interested in some form of art. It could be a movie, it could be a drag show, it could be a beauty pageant. There’s some artistic entertainment medium that everybody is interested in.

So if you’re going to get a point across that you know is personal to your people, you’d want to do it in a way that keeps their interest. And if you have just the right sounding tune, a really good single that has this huge message behind it, it will reach people that much harder than just going out in the street with a megaphone and blurting out a bunch of your opinions.

MA: Are there other walls and challenges that you feel you and others are addressing through art?

AH: Yes, I think one of the biggest walls that people like you, myself, and a lot of others are currently breaking is generational trauma. Part of that comes from a time where it wasn’t cool to be native where it was either frowned upon or attempts were made to beat all of that culture out. But we are at a point where we can use our culture to do the exact opposite, and heal that trauma, to instill pride.

If there’s one thing that can never harm you, no matter how much you do it, it’s the arts. The music, making a totem pole, singing, dancing, and all of that expression. It’s a much better choice than some of the alternatives. I believe in the power of the arts for that.

MA: With it being the end of Black History month, I’m wondering if you could share a bit more about your experience and your identity. Is there something you think that is misunderstood about being Afro-Indigenous?

AH: That it’s OK to be both. I feel like there’s instances where even the Afro-Indigenous people themselves feel like they have to choose one to move towards more than the other. And I don’t think that’s necessary. If you want to really embrace your full self, for as long as you shall live, just let it all be known.

And I love the acknowledgement but at the same time, there are some people who think the only cool thing about me is that I’m Afro-indigenous, and really, that’s just the start. Yeah, I’m Afro-indigenous and I’m constantly working on how that can manifest in a really cool way that people haven’t seen before, and that’s my music.

MA: Looking forward, what do you imagine and hope for your community in 10 years? Tell us what this world looks like?

AH: Part of it is already happening and that is a new art center in town and I want to see it put to good use across all sorts of artforms. I’d just love to see a humongous influx of artists in more ways, more plays in our Indigenous languages and more fusions. What about Alaska Native anime, that would be so rad!

I really do think that’s where we’re headed. I feel like people are starting to break out of the box and we are unsticking ourselves from the art of the 1800s. We respect the hell out of that art, and those practices, but we’re still moving forward with all of our different types of art.

And like we talked about earlier with art marking our place in history, it’s important to let the next generation know that it’s OK to adapt and to change things. Put formline on your car if you want to, no they didn’t have cars back in the day but, slap it on and let’s bring our art into all spaces.

This “new wave” should know that if you want to start a mission on behalf of your people, it’s really important that you do it in a way where you embrace your values and you just wear your culture on your sleeve everywhere you go- effortlessly. You don’t have to prove it and you don’t have to disprove it. You just let it be. Be you, be proud and that’s what moving from oppression to expression can look like.

MA: It’s been so rewarding to talk in depth with you about the purpose of your work and the heart behind your lyrics. Gunalchéeshand Hawaa, and tell us what is next for you and how people can follow along!

I will be releasing some new singles here in the short term. I’m on Spotify and YouTube as Air Jazz and working on some new content and looking forward to the next Rock Aak’w Fest in 2023!

Marina Anderson, born and raised on Prince of Wales Island, is a tribal leader, activist, artist and producer of the film “Setting the Table,” released this year which explores Indigenous sovereignty, the Roadless Rule, and stewardship of the Tongass National Forest. The Sustainable Southeast Partnership is a dynamic collective uniting diverse skills and perspectives to strengthen cultural, ecological, and economic resilience across Southeast Alaska. It envisions self-determined and connected communities where Southeast Indigenous values continue to inspire society, shape our relationships, and ensure that each generation thrives on healthy lands and waters. SSP shares stories that inspire and better connect our unique, isolated communities. Resilient Peoples & Place appears monthly in the Capital City Weekly. SSP can also be found online at sustainablesoutheast.net.