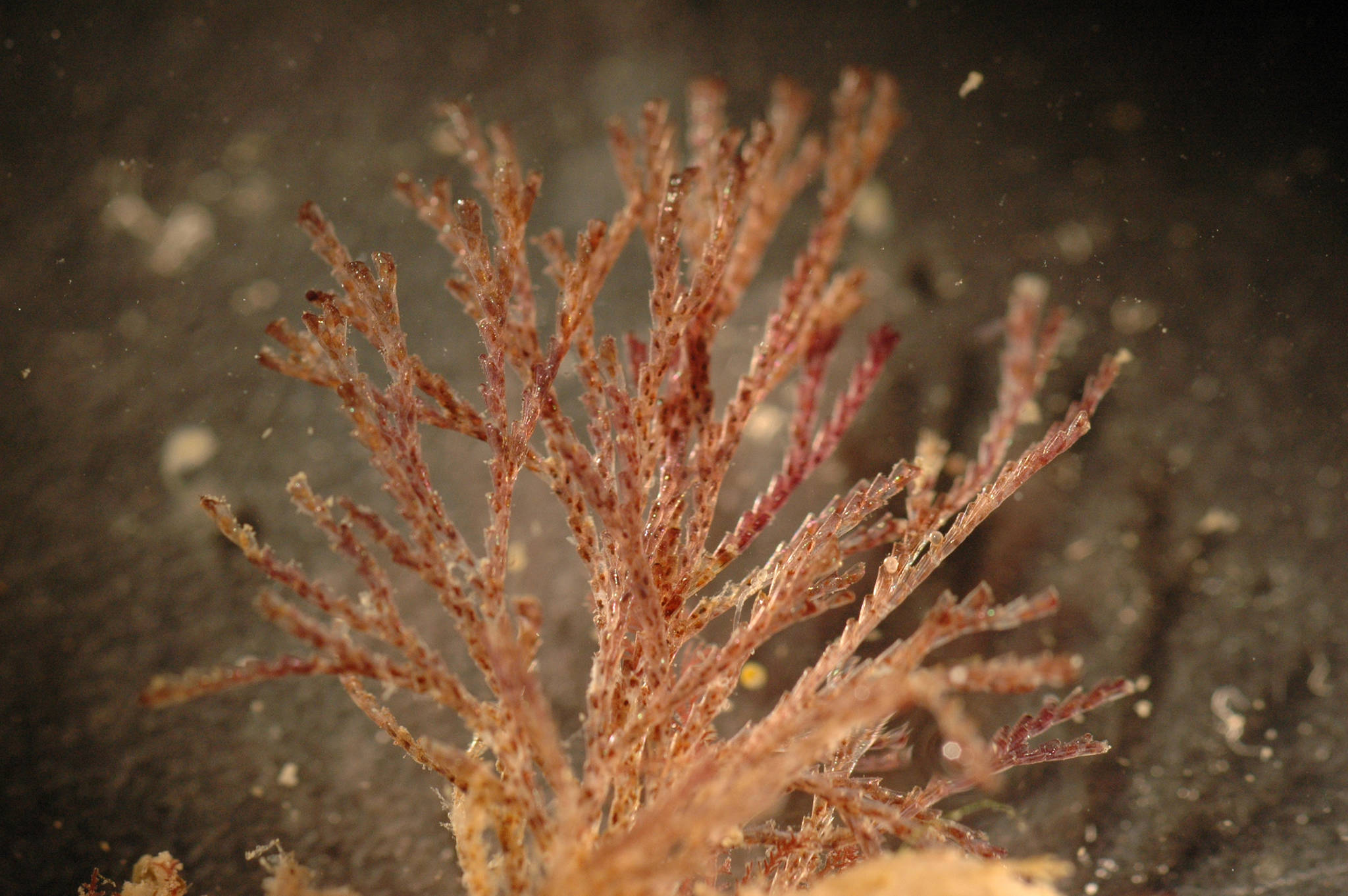

They’re called sea lace, moss animals and Bugula neritina to scientists — and they’re not supposed to be here.

But they are here, scientists say. The invasive species has been spotted in the southern reaches of coastal Alaska, a team of researchers has discovered.

According to a study published Sept. 27 in the academic journal Bioinvasions Records, the plant-like animal has been catalogued in Ketchikan for the first time ever. Invasive species, plants and animals that may move in to a geographic area where they aren’t indigenous, can sometimes wreak havoc on local ecosystems.

University of Alaska Fairbanks professor Gary Freitag, one of the study’s authors, said they don’t yet know how the sea lace will affect marine life around Ketchikan. There’s potential that it could do nothing, or it could outcompete native species for food or territory.

“We really don’t know the impacts of this,” Freitag said.

[Invasion from ‘Borg of the ocean’ baffles scientists]

The tiny organisms attach to hard surfaces like docks, rocks and the hulls of boats, forming colonies and filter-feeding off passing food particles.

The discovery comes from a year of analysis by a scientific team from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Temple University and the UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, where Freitag works as a marine advisor for the college’s Alaska Sea Grant.

The team suspended a series of small plastic plates around Ketchikan attached to bricks, Freitag said. Floating in the water column, the plates served as hosts to a smattering of sea species. The team then lab-analyzed the diversity of animals on the plates, providing them a picture of the different animals present near Ketchikan.

The team first encountered Bugula neritina in 2015 at Ketchikan’s Bar Harbor Marina, according to the paper.

The First City is the northern-most site for the study, which looked at biodiversity in marine waters in California, Panama and Mexico. The team wanted to find out how coastal marine life differs at different latitudes, Freitag said.

“There’s been a lot of theories as to whether diversity of organisms, the amount of organisms and the number of different species, varies with latitude in a region along the coastline. They were working out whether that theory is correct,” Freitag told the Empire in a Thursday phone interview.

The researchers don’t know why or how Bugula neritina moved north to Alaska. It could have arrived on the bottom of a passing vessel. Ketchikan is the first stop for foreign-flagged cruise ships and barges and fishing boats heading north.

Warming waters may be making the migration of invasive species easier, Freitag said. Several marine species new to Alaska, like market squid, are thought to have arrived here after chasing warmer waters north. Researchers believe Ketchikan is a bellwether for such migration.

The discovery is the northernmost record of Bugula neritina in the Pacific Ocean.

“I don’t know whether there’s any real, direct evidence that climate change is causing the spread of invasive species. It’s suspected very heavily, there’s indications that it plays a role,” Freitag said.

[Squid fishery proposed for Southeast]

Alaska has fewer non-indigenous marine species than any other coastal U.S. state, the team wrote, and Ketchikan is a “key location in Alaska for early detection of marine species with the potential to spread poleward from lower latitudes.”

The paper also documents the spread of several other invasive species in Ketchikan’s marine waters. Some of them are potentially problematic for native sea life, Freitag said.

The discovery marks the culmination of years of observation not only by professionals like Freitag, but citizen scientists who’ve tracked invasive species in Ketchikan since at least 2003.

The team documented the continuing spread of three non-indigenous tunicates, invertebrates known as sea squirts. One of those species, Ciona savignyi, the Pacific transparent sea squirt, hasn’t been documented in Alaska waters since 1903.

Sea squirts can cause problems for coastal economies in ground fisheries and oyster and other mariculture farms. Freitag said they haven’t yet documented any adverse effects from the Bugula neritina or any of the sea squirt species. But the potential for disruption is there.

“It’s really not understood what the potential dangers are of any of this stuff, but it potentially has a lot of impact,” Freitag said.

• Contact reporter Kevin Gullufsen at 523-2228 and kgullufsen@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @KevinGullufsen.