When John Straley’s newest novel about his fictional Southeast Alaska town of Cold Storage debuts in December it will be the first time in 45 years the former Alaska State Writer Laureate is no longer a resident of the region.

But, unlike his novels, there’s no mysteries or conspiracy theories involved. In an interview from his home in Stika this week Straley, who will turn 70 next year, said he’s returning to his birth state of California at the end of September due to health and family reasons.

“We’ve gotten to the point where the winters are too hard on our bones,” he said.

Straley’s move to the state’s wine country region of Carmel Valley are motivated by his son and daughter-in-law living in the area, his wife’s Parkinson’s disease taking its toll, and his willingness to accept moving on to what he calls a next adventure after so many in Alaska.

“I’m heartbroken to leave it, but I’m not the only one whose life I have to consider. I have my wife and family,” he said.

Straley said he hopes to make a return visit for the release of “Blown By The Same Wind,” the fourth of his novels about the fictional community of Cold Storage, which is something of an amalgamation of Pelican, Tenakee Springs and Port Alexander. The book’s setting in 1968 brings the outside turmoil of the Vietnam War, racial strife and a JFK-esque conspiracy about the mummified body of presidential assassin John Wilkes Booth to the remote village.

Those elements and the everyday zaniness of life in Cold Storage mesh into a narrative about the mysterious arrival of Thomas Merton, a real-life monk and peace activist who visited Alaska for a brief period in September of that year before departing for a monastic conference in Bangkok where his death in a “tragic accident” remains yet another conspiracy topic.

“He was always surrounded by all these conspiracies that the government was out to get him,” Straley said on making the monk the main protagonist of the novel. “I just thought he was a natural.”

Real people commonly are characters in Straley’s novels, which he acknowledges requires sensitivity when placing them in controversial settings (including, in this case, narrating a mix of real and fictional moments in the days immediately before Merton’s death). The same applies to accurately depicting the racist and nationalist personas and language of that era, which are among the things often getting flagged in the current era of increasingly politically correct language.

“It’s not a bad time to revisit these figures,” Straley said. “War and peace are always an issue. I thought he’d be a good person to guide us through this.”

The novel’s conspiracies, spanning time from the presidential assassin to whether the visiting monk is a target of the federal government, also are well-suited for modern day society and politics, the author said.

“It’s an essential question that interested me,” Straley said, referring to conspiracy theories. “How much is true and how much do people want to be true? That’s an essential theme right now. What is truth? What is accuracy?”

Making Booth in the narrative wasn’t just Straley tossing in his own conspiracy out of thin air.

“In my late teens in ‘68 it was a very vivid time as far as the Chicago riots making a big impression on me,” he said. “This whole fury over war and peace and assassinations. Then when I read about this conspiracy theory about Booth where people believed he hadn’t died and was seen 10 days after Lincoln’s assassination I thought this just fits into my theme.”

The narrative is markedly different from his previous Cold Storage novel published in 2020, “What Is Time to a Pig?” That book, which critics and fans describe as markedly different from the first two novels set in the town, features a dystopian-tinged narrative set in the near-term future after a brief war North Korea starts by firing a missile that hits Cold Storage with an unexploded warhead. Reader reviews on Amazon are, perhaps not surprisingly, strongly divided.

“It was different and it came out right as the pandemic began and events were canceled,” Straley said. “I don’t think people were excited about reading another crisis of a president starting a war just to help his election chances.”

“Blown By The Same Wind,” which Straley said he started working on three or four years ago, is more similar to the first Cold Storage novels where the eclectic humor of the community, something highlighted by reviewers, is a stronger element. It also will apparently be the final book in the series written in Alaska, although whether he’ll pen further ones about Cold Storage, Alaska, private eye Cecil Younger past works from his new home is unknown.

“I’m not sure,” he said, “I’m working on a book that is placed mostly in Seattle and the state of Washington. I’m not sure what I’m going to write about, but I’m sure Alaska will be an important part of it.”

Straley was born in Redwood City, California, grew up in Seattle and moved to Sitka with his wife in 1977. He worked as private investigator and then became a state investigator for the Alaska Public Defender’s office in Sitka until 2015. His first novel “The Woman Who Married a Bear,” the first of seven in the Cecil Younger series, was published in 1992 and won the 1993 Shamus Award.

He was the writer laureate for the State of Alaska between 2006 and 2008, after which much of his work began focusing on poetry.

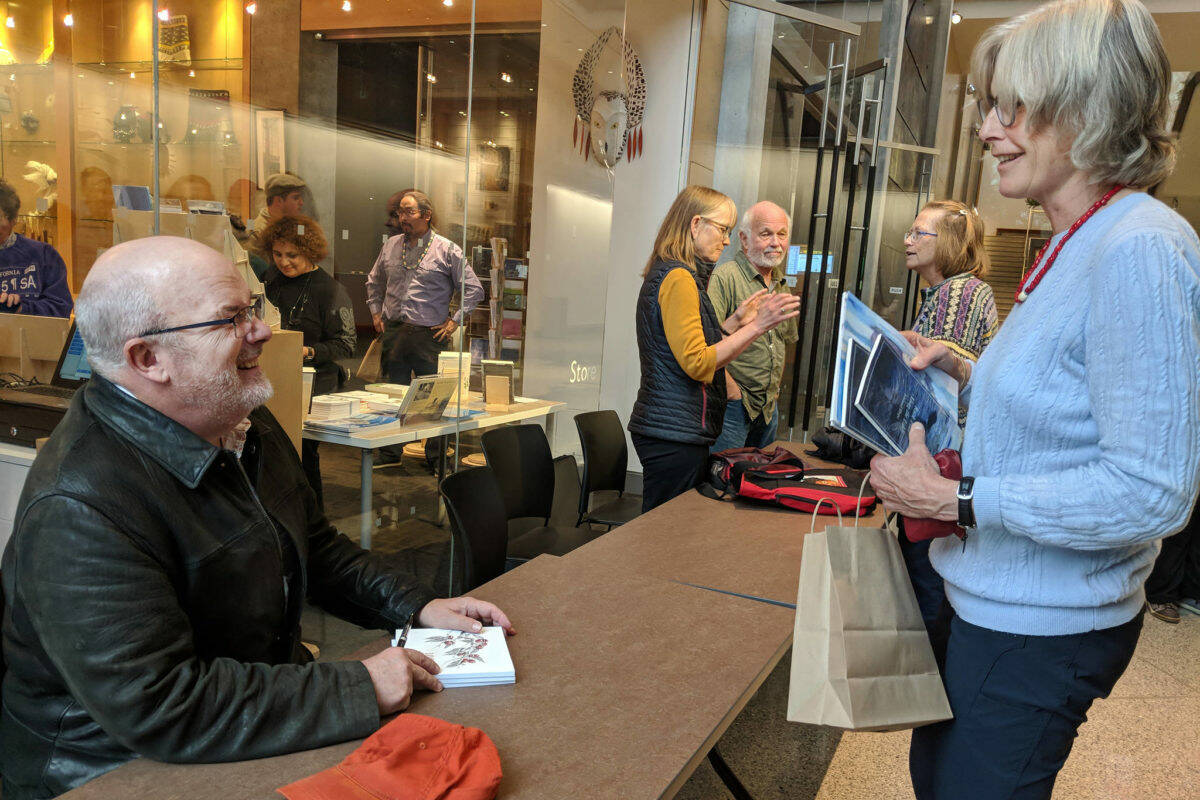

Straley is scheduled to depart Sitka on Sept. 25 and, while he did a recent reading at Old Harbor Books (which has been there about as long as he has) and a farewell gathering, he isn’t planning any other events before he leaves. But that’s for practical and packing reasons, not any haste to leave his experiences here behind as he starts anew elsewhere.

“I don’t think I’ll ever find a group of communities that interest me as much as Alaska,” he said.

Juneau Empire reporter Mark Sabbatini can be reached at mark.sabbatini@juneauempire.com