For the 20th straight year, in December 2019 I carried a notebook into the halls of the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union. Most of those years the conference was in San Francisco (as it was this year).

Back in 1999, when one billion fewer people lived on Earth, the 5,000 scientists who visited the meeting mostly reported on earthquakes and rocks and blue-and-red flashes that shot upwards into space from lightning strikes.

In December, more than 25,000 scientists traveled to San Francisco for the weeklong conference to present their research on classic hard-science subjects and a few surprises, including the migration of creatures ranging from Alaska earthworms to humans threatened by rising sea level.

Here are a few scribbles from my notebook on a subsample of the more than 1,000 Alaska talks and posters:

A telltale pockmark in the face of Hubbard Glacier: As glaciologist Mark Fahnestock of UAF’s Geophysical Institute was preparing a time-lapse video of shrinking Alaska glaciers for the conference, he noticed something odd about Hubbard Glacier.

Hubbard Glacier, north of Yakutat, flows for more than 75 miles out of the high border country of U.S. and Canada. Its tongue touches salt water in Disenchantment Bay, and thousands of tourists on cruise ships watch each summer as towers of its blue ice lean forward and plunge into the ocean.

Hubbard is one of a few Alaska glaciers that scientists have said will continue to advance regardless of how much air temperatures warm, because it has so much ice to deliver from up high in the mountains. Twice in the past 34 years, Hubbard has shoved itself into Gilbert Point, damming Russell Fiord until the rising water burst a new channel to the ocean.

A few weeks before the conference, Fahnestock noticed a bite out of the broad face of Hubbard Glacier when viewed from a satellite. This “embayment” is similar to what scientists saw in Columbia Glacier just before its 12-mile retreat from the sea that began in the 1980s. Glaciologists called that a catastrophic retreat.

Fahnestock said the missing chunks of ice at the face of Hubbard Glacier might be evidence of a very strong year of melt having formed a subglacial river that causes even more melting underneath.

“That image suggests the first sign of weakness for that glacier,” Fahnestock said at a press conference in San Francisco.

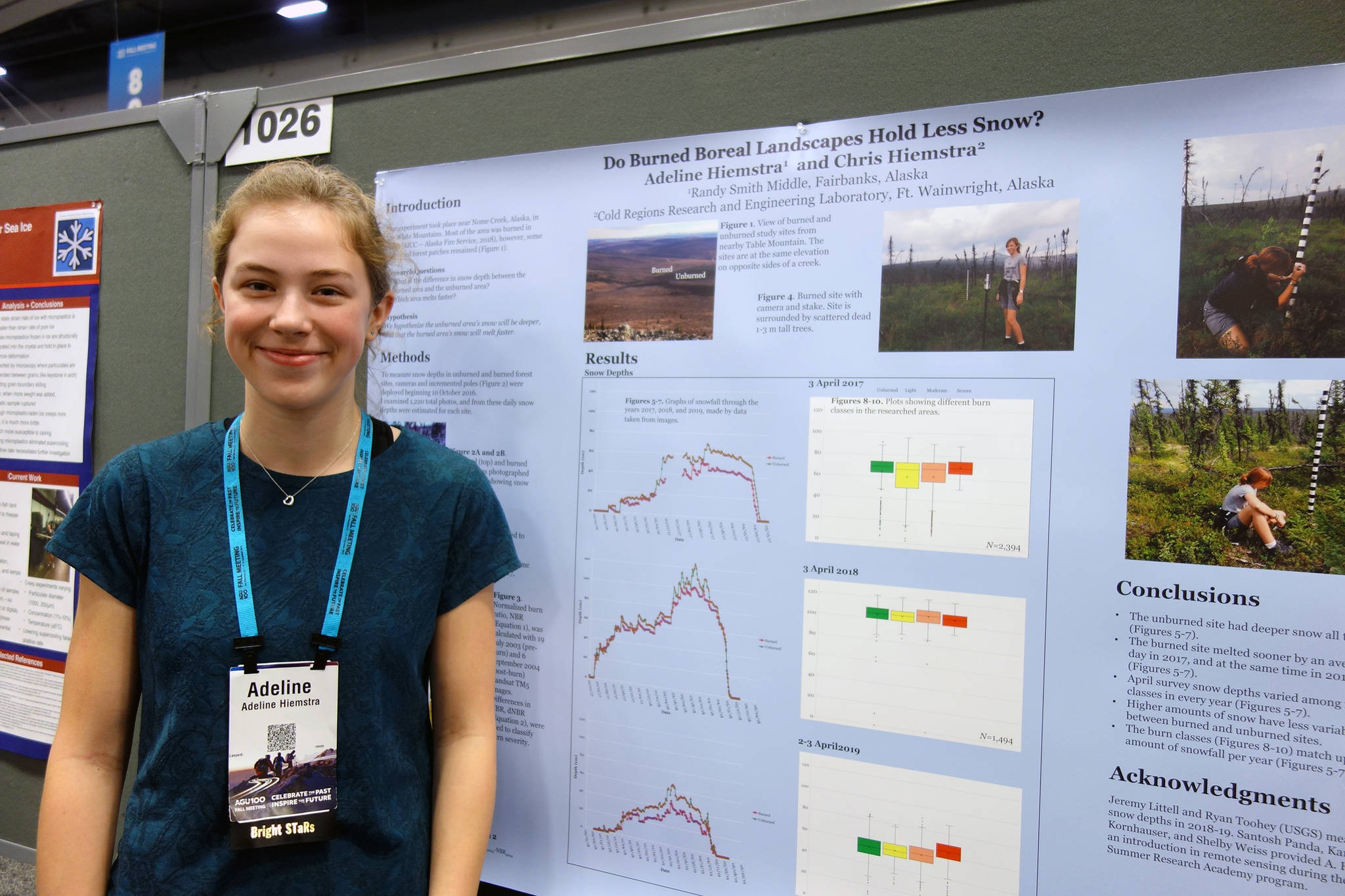

Burned areas hold less snow: In the 20 years I have roamed the cavernous poster halls at the meeting, the average age of the scientist I’ve seen standing in front of a poster has been about 40. This year, I was surprised to see Adeline Hiemstra, a 14-year-old eighth grader.

Hiemstra, who goes to Randy Smith Middle School in Fairbanks, credited her parents, Theresa Kay and Chris Hiemstra (a snow ecologist) for inspiring her to submit her study to the American Geophysical Union’s Bright Stars program. The program allows kids to present at the conference without paying the fee adult scientists pay.

Each fall Hiemstra and her family pick blueberries in the hills near Nome Creek, Alaska. Looking around at the burned-matchstick forests of black spruce and other unburned hillsides, she wondered if the bare forest would hold more or less snow compared to healthy forests with tree needles intact. She wanted to see if blueberry crops were different in either type of landscape.

She set out cameras in both a burned forest and an unburned one, to help her measure snow using graduated sticks that were in the camera frame. She found that burned forests held less snow during the winter, and burned areas melted out sooner in one of the three years she monitored. She did not have enough information to relate the sites to blueberry production.

Why did a teenager do a science project that involved swatting bugs, feeling the sting of cold wind, and investing lots more time than just her school homework?

“Because it’s fun,” she said in San Francisco. “I could do the research and figure it out for myself. I didn’t have to rely on other people’s opinions. You have the facts and data right in front of your face.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.