It’s funny how a certain sight, sound or smell can take you back in time. I was coming out of the Dockside Restaurant in Craig a couple weeks ago when my thoughts took me back 50 years. Maybe it was the sight of a troller on the grid at the City Dock, or maybe the cry of a sea gull, but I suddenly found myself thinking about Mama Abel.

In 1963, the summer I was 9 years old, there weren’t many businesses in downtown Craig. On pilings along the waterfront, from east to west, stood the Union Oil dock and office, the Craig Inn, and a little building where a few years later Greg Shapley would operate a juke joint called the Pussycat A Go Go. Then came a small stretch of beach, then J.T. Brown’s General Store (better known as Jonesy’s), Cogo’s Restaurant and Hotel, the Lunch Room that would eventually become Ruth Ann’s, and finally the Standard Oil Dock. Across the street from Jonesy’s stood Yates’s Dry Goods Store, and next to Yates’, where the Dockside Restaurant is now, was Abel’s Confectionary, a lopsided little green and white clapboard store owned and operated by Mama Abel; an old, stooped Norwegian lady with thin yellow-gray hair and thick glasses.

I loved hamburgers, and Mama Abel served the best ones in town. Not that there were a lot of choices. The only other place that was regularly open was the Lunch Room, operated by my aunt Florence Mielke. The Lunch Room had a deep fryer, so you could get french fries, but the hamburgers weren’t as good. Florence’s burger patties were pre-formed and frozen, and they tasted a little old and tough.

Not so with Mama Abel’s. Her hamburgers were made right on the spot. After you ordered one, she would hobble into the back to prepare it. A faded curtain that was normally pushed to one side hung on a wooden rod in the kitchen doorway, and looking past it you could see her pull a chunk of fresh hamburger off the main glob and form it into a patty in her hands. She would fry it in a cast iron pan on top of her oil stove, and after buttering the bun she would grill it face down alongside the burger. When it was done, she served it on a heavy china plate with nothing but two long slices of dill pickle. Containers of Heinz Ketchup and French’s Mustard stood on the counter next to the salt and pepper. The taste was out of this world, a homemade version of the simple combination that entrepreneur Ray Krok would turn into the multi-billion dollar hamburger empire McDonald’s.

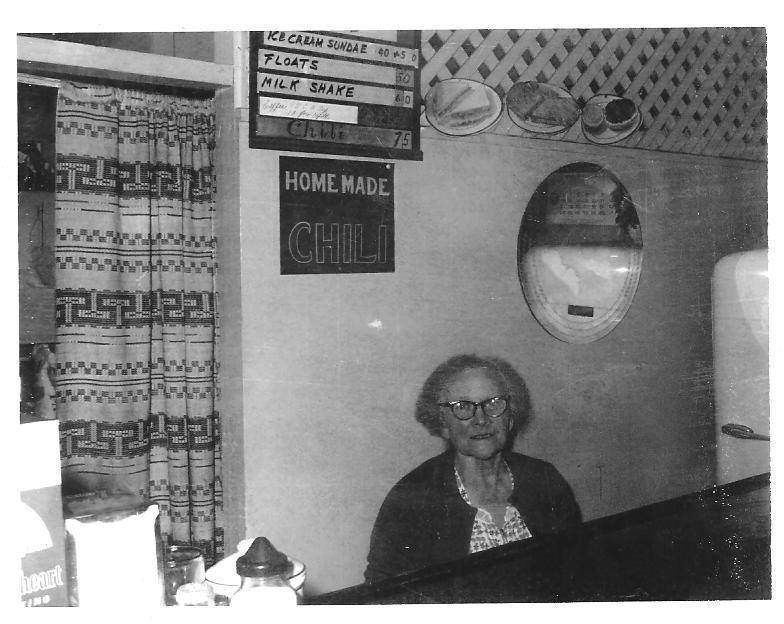

The old building wasn’t much to look at from the outside. It was little more than a 20 x 30 foot shack, and the perimeter of the foundation was slowly sinking into the damp ground below. When you entered, the tongue and groove hemlock floor, worn and darkened with age, gradually inclined upward to a hump in the middle, and then tapered down toward the counters that bordered two sides of the room. The interior was avocado green, and the built-in wooden counter stools were solid dark blue except for the nicks, scratches and worn spots. The upper half of the back wall that separated the dining area from the kitchen was covered with painted latticework, upon which hung a big bright red Coca-Cola orb, and Mama Abel’s menu featuring her famous hot chili. The menu frame had wooden slats, which held strips of aging cardstock with menu items printed in elegant black calligraphy, except for the “Hot” in Hot Chili, which was written in red. Folks claimed the chili was delicious. It sounded dangerous to me. If someone happened to order a bowl, I’d watch to see if they showed any signs of discomfort. I witnessed only satisfaction, so it must have been good. Even so, if I had 50 cents, there was no question it was going for a hamburger.

Mama Abel lived in the back of her little store, and it seemed to me the only daylight she ever saw was each afternoon at pigeon feeding time, when she would stand in her front doorway and toss birdseed out onto the hard-packed dirt street for 30 or 40 furiously pecking pigeons. I’m told that for years she did make an annual buying trip to Seattle, but by the time I came along she was staying home and ordering by mail. My mom grew up in Craig, and she said Mama Abel didn’t get out much in those days either, except every year at carnival time, when she would fix up her hair, put on her mink coat, and walk up the hill to the school and spend the evening playing bingo.

Mama Abel had an old Wurlitzer jukebox that would light up like a rainbow whenever you played it. Inside the jukebox, a carousel boasted a huge ring of black vinyl 45s. After dropping in a nickel in the coin slot and punching the right numbers, the carousel rotated, stopping when the chosen record reached the peak of the ring. Then a robot-like arm reached out and snatched the 45, pulling back into a sharp 90-degree turn and laying the record out perfectly on the turntable, right before your eyes.

A new shipment of records arrived in the mail once a month, and I hung around when the teenagers came in to see what was new. My favorite was “Hello Stranger” by Barbara Lewis.

“Seems like a mighty long time”, the lady from Motown crooned, “Shu bob, shu bop, my baby ooo!”

I thought “Green Green” by the New Christy Minstrels and Jan & Dean’s “Surf City” were pretty cool, but in general I was more interested in Mama Abel’s hamburgers and milkshakes. The pop music explosion of 1964 was still a year away, and nobody seemed nearly as crazy about hit songs as we were about to become.

There was a faded sign painted on the outside of the building that read “ABEL’S CONFECTIONARY.” I wasn’t sure what a confectionary was, but figured it had something to do with good things to eat. Open boxes of penny candy crowded a shelf just over the counter. Jawbreakers, Pixie sticks, Bazooka bubble gum, red and black licorice vines, little Tootsie Rolls, juicy wax tubes and sour grape gumballs were just part of the display. Five or six flavors of Tootsie Roll pops, costing two cents, completed the front row. On the back counter were the candy bars, and stuff that cost five cents. Snickers, Milky Way, Forever Yours, Big Hunk, Look, 5th Avenue, Payday, Heath, Baby Ruth, full size Tootsie Rolls, along with Sugar Daddies, Sugar Babies, Dots, Red Hots, Jujy Fruits and Good’n’Plenty; Mama Abel had it all! Large grape and raspberry suckers also cost a nickel, and you unwrapped them hoping to find a little strip of paper saying, “Winner,” which got you a free one.

Mama Abel served soda pop in stubby brown bottles with no labels. You knew the flavor by the orange, strawberry or grape colored cap, which had to be popped off in the metal opener that was bolted to a post behind the counter. She sold chocolate, strawberry and vanilla ice cream cones for five cents a scoop. The jar of water that the ice cream scoop stood soaking in looked pretty gross, but she’d give it a good shake before she dipped into the ice cream tubs to make your cone.

Mama Abel had a pale green milkshake maker with tall stainless steel mixing cups. If you ordered a chocolate milkshake, she would start with several scoops of vanilla ice cream, add chocolate syrup, fill the cup with milk, and thread it onto the mixer, snapping it into place. The mixer was noisy, and the stainless cup rattled around so much you were sure it was going to fly off and make a big mess. But somehow it always seemed to hang on, and before long she’d be pouring your milkshake into a fancy glass and handing it to you with a long spoon. I would quickly take a couple big gulps and ask for what was left in the bottom of the mixing cup.

Mama Abel used to sit and rest on a stool behind the back counter until someone came through the door. Then she would sigh, get up and come over to see what you wanted. Although she must have stocked 20 different kinds of penny candy, I got scolded once for coming in with just a penny. Maybe my taking five minutes to decide what I wanted had something to do with the scolding.

All summer long Mama Abel would make Kool-Aid popsicles in Dixie Cups. The popsicles had to be warmed up in your hands before you could finally break them loose by twisting on the wooden meat skewer frozen into each one. When the weather was nice, she would run out of popsicles, and we would start pestering her about the new batch. From time to time she’d hobble into the side room where the chest freezer was. If she came back through the curtain empty handed, you knew it was going to be another hour.

In May of 1971 as I was about to graduate from Ketchikan High School, a card came in the mail addressed to “Rolf” Mackie. It contained hand written best wishes, and a crisp $10 bill. Mama Abel had remembered me!

I was in and out of Craig for the next few years, and wasn’t there when Mama Abel died. The confectionary passed on to her daughter-in-law Goldie. Somewhere along the line a City dump truck went off the road and plowed into the back of the little building, damaging it beyond repair. A new Pan-Abode cedar building was constructed in its place. Today it’s the Dockside Restaurant, and the corner of 4th and Front Street continues to be a place where you can find good things to eat. But there will never be a place like Mama Abel’s. To a kid in Craig back then, happiness was finding a nickel, a dime, or sometimes 50 cents, and having just the right place to spend it.

• Ralph Mackie operates the Hill Bar in Craig, and gill nets out of Coffman Cove.