I came here 40 years ago, when I just moved up from Juneau,” Kes Woodward says in a South-Carolina accent soft as butter. “These trees were just saplings.”

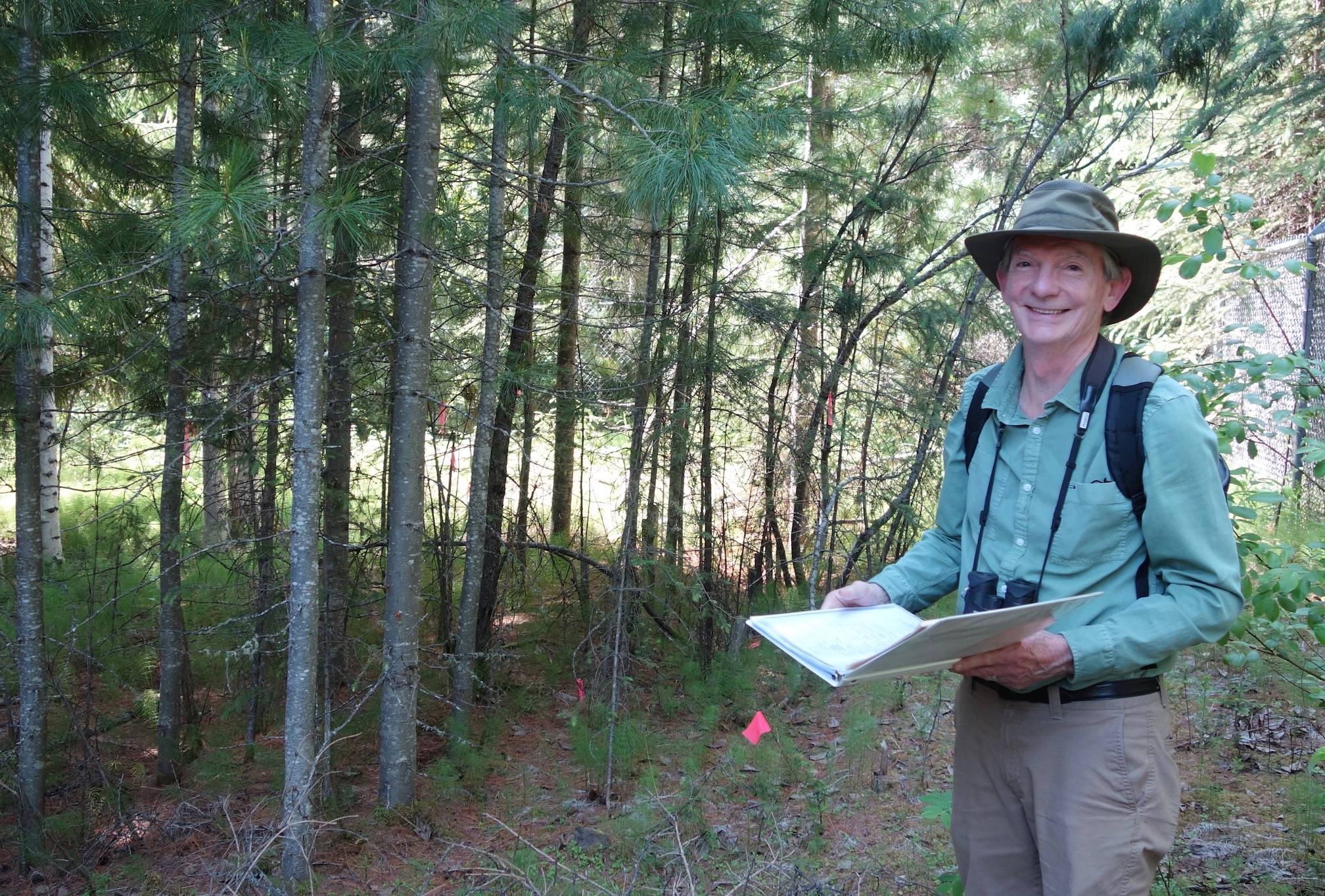

Woodward, 69, a painter and emeritus University of Alaska Fairbanks art professor, is guiding me on a walk through an unusual grove of trees. The tall stems standing before us are not often seen in middle Alaska.

In the delicious, 80-degree air of the warmest day in two years, we are surrounded by lodgepole pines from the Yukon, Siberian larch from Finland and silver birch also from Finland, the latter featuring straight-grained wood the locals favored for sled runners.

In 1964, just after Lyndon Johnson swore the oath to follow John F. Kennedy, Alaska forester Les Viereck and others planted tree seedlings at the north end of this old farm field.

The two-acre exotic tree plantation is part of a much-larger “boreal arboretum” on the UAF campus, which mostly consists of native spruce, birch, aspen, poplar and willow trees.

Having borrowed the key from a researcher with UAF’s Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, Woodward has invited me to join him inside the chain-link fence.

I have been curious about these trees for years as I circled the fence on the trails alongside — especially in fall when the larches flame orange.

Some of these trees seem to have cracked the code of living in the subarctic, unlike some sugar maples I have over the years carried home from New England in glass jars. Alaska’s extreme cold and drastic shifts of daylight are too much for most of the species on the planet, including trees.

But a few imported trees here stand tall, straight and perfect: Siberian larch and lodgepole pine seem to be the champions, so far.

“Larch in their first 40 years will outgrow local white spruce in trunk volume by six times, and lodgepole for 35 years will outgrow locals,” Woodward says.

I later check his numbers in a paper written by Alaska forest geneticist John Alden, who dirtied his fingernails planting some seedlings here. Woodward is correct.

He also quizzes me:

“There is only one tree not native to Alaska that scientists documented as having survived and spread to new sites. They call that ‘naturalizing.’ Guess which tree it is?”

“Lodgepole pine?”

“No, that’s what I thought. It’s mountain ash.”

That ornamental species decorating many Alaska streets has red/orange berries. The fruit is a favorite of Bohemian waxwings, which perform much of the seed spreading.

As we walk, our steps quieted by shed orange needles of larch and pine, Woodward and I both say how peaceful it is. Just outside the fence, a runner passes without noticing us. We hear his labored breaths. Above, an alder flycatcher sings its two-note song, having just arrived from the Gulf Coast of Mexico to perch on northern branches.

These exotic trees — some now 70 feet tall — are a nice legacy for the men who planted shin-high seedlings years before Woodward last visited the plot in 1981. Les Viereck, a renowned ecologist who wrote “Alaska Trees and Shrubs,” died in 2008.

Why — in this era of consciousness of invasive species that might crowd out the natives — did Viereck and others plant different trees in Alaska?

“Introduction of nonnative tree species may improve the diversity, stability, and productivity of managed forest ecosystems,” John Alden wrote. He added that new tree species might also “favorably alter the habitat for the indigenous wildlife.”

Though many of the trees in UAF’s plot are thriving, Woodward points out that these woody organisms have enjoyed the lifelong protection of a coarse-mesh metal fence. It prevents moose from nibbling tree shoots and thrashing trunks to a pulp with their antlers.

Patches of hardware cloth also cling to the bottom of the fence. The wire mesh excludes snowshoe hares, which sometimes clip seedlings at the stem or girdle young trees, especially at the peak of hares’ 11-year cycles.

This gentle, south-facing slope on well-drained Fairbanks silt loam has been an ideal place to be a tree for the last half century. The airy lodgepole pines seem to be patiently waiting for their Whitehorse brethren to drop their seeds northwestward.

As these trees shot upward during the last 40 years, Woodward was painting others in his studio overlooking the Tanana River Flats.

“I have always been into trees,” he says. “My name is Woodward; it’s probably in my genes.”

Woodward remembers walking through stands of fragrant pines with his grandfather, a lumberman in South Carolina. His grandfather would select trees for harvest.

Woodward has less-consumptive plans for the trees at the UAF site.

“This is like a dream come true for me to be in this two-acre plot and see how trees from all over the circumpolar north are doing,” he says. “I want to get to know every single tree here.”

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell ned.rozell@alaska.edu is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.