Fifteen Southeast Alaska sovereign tribal nations petitioned an international commission for human rights to take action against Canada regarding violations by six mines in British Columbia, Canada.

The petition was filed on Wednesday by the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission (SEITC), which consists of representatives from 15 prominent Alaska Native tribes. Among those tribes are the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska based in Juneau, and those in Sitka, Ketchikan, Douglas, Yakutat and Wrangell.

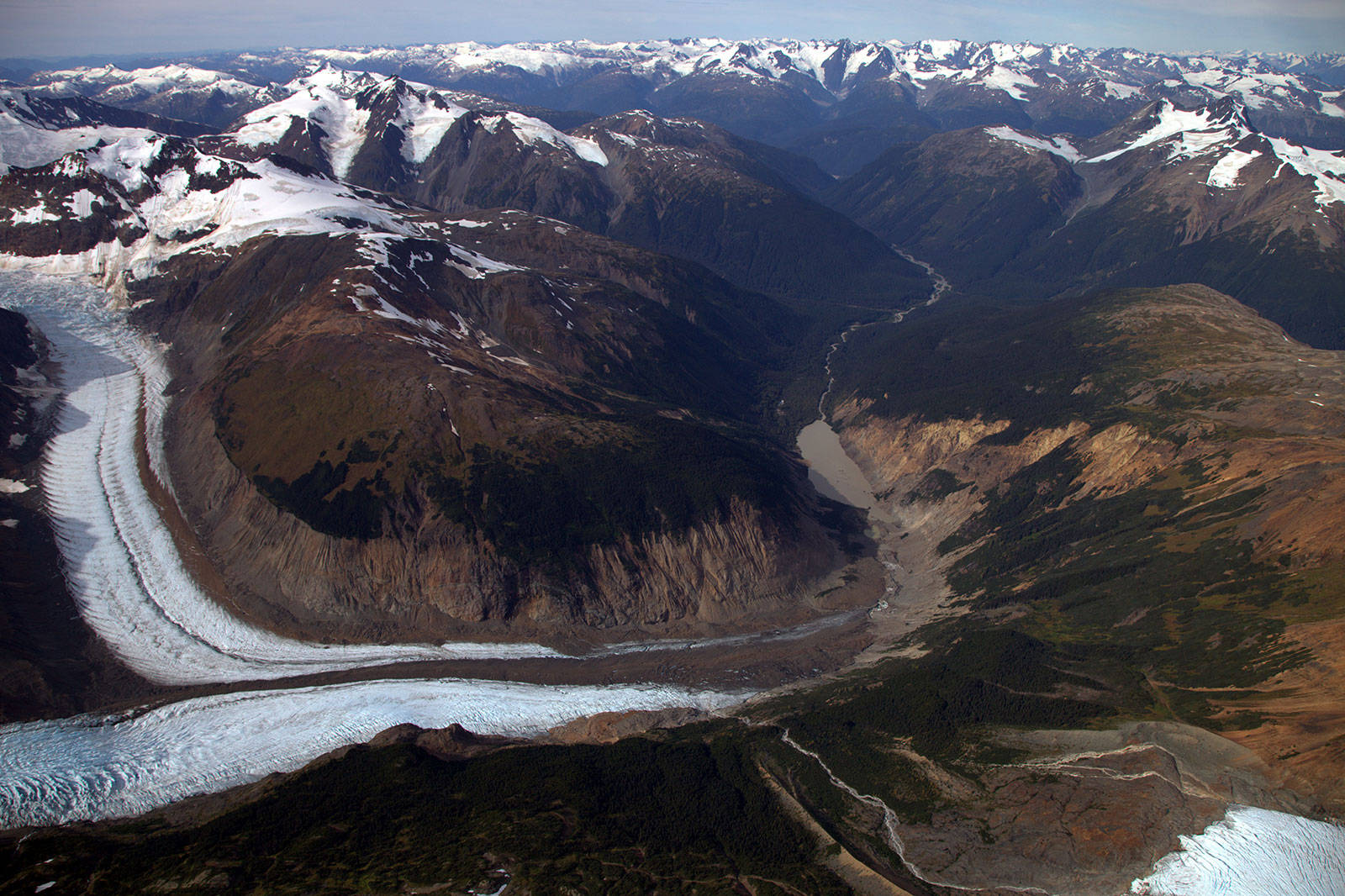

The petition requests that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) assists the tribes in obtaining relief resulting from the violations by the mines, including the Tulsequah Chief Mine which has been leaching toxic water into prime Alaska and Canada salmon habitat for more than 60 years. The petition claims that the six mines are likely to release harmful pollution into the rivers, which threatens the fish essential to maintaining life in the tribes.

[Opinion: Clean up that damn mine]

Failing to prevent pollution in Alaska watersheds could constitute a violation of indigenous people’s rights, the group alleges. The petition said the government of Canada did not consult with or seek the free, prior and informed consent of the SEITC tribal nations during the approval of the mines or permitting of the mines, as required by international law under the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights is an international human rights advocacy group headquartered in Washington, D.C. Its mission is to promote and protect human rights in the American hemisphere.

“We are hoping the commission will pick up the case,” said Ramin Pejan, attorney for Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law firm that filed the petition for SEITC. “The goal here really is to inject or raise human rights violations as a key part of the narrative with these mines, and that has been missing in the approval process thus far.”

Earthjustice and the SEITC have been working on drafting the petition for about a year. It is connected with some of their previous work involving these mines. One attempt involved drafting a different petition to the U.S. Department of the Interior for protection under the Fisherman’s Protective Act and the Boundary Waters Treaty. But he said, that petition was more a political process than a legal process.

“This is much stronger, we think, particularly when it comes to protecting the rights of the tribal members,” Pejan said. “One of the reasons we brought the petition to [the IACHR] is because they have a strong and rich body of precedent regarding indigenous people’s rights, particularly around environmental harm.”

He said there’s a dozen cases referenced in the SEITC petition that the IACHR has worked on and had success with that relate to the same human rights violations the Southeast tribes are alleging.

“The ultimate goal is to get a more in-depth review on the projects to assure that the effects are not going to impact us in a way that violates our rights for our food security and cultural existence,” said Jennifer Hanlon, vice chair of the SIETC.

There are six mines included in the petition. Two of the hard-rock mines are already operational: the Brucejack Mine and the KSM Mine. And four are proposed in the upper reaches of the watersheds of the Taku, Stikine and Unuk rivers. The four proposed mines are the Tulsequah Chief Mine, Red Chris Porphyry Copper-Gold Mine, Schaft Creek Mine and the Galore Creek Mine.

Biologists say these watersheds are teeming with biodiversity, including dozens of species of fish. Mainly important to the petition: salmon and eulachon, which have been staple commodities of the tribes and remain centerpieces of their cultural practices and spiritual beliefs, according to the petition.

“Salmon is the staple harvest in our traditional culture,” said Tammi Meissner, a member of the SEITC from the Wrangell Cooperative Association in a testimony included in the 215-page petition. “You could say it is the heartbeat of our culture. If the salmon heartbeat is gone, then ours will be gone, too.”

One of the main focuses of the petition is that Canada did not consult with the tribes or conduct any assessments of the mine’s impacts in the watersheds in Alaska, which they claim violates their human rights and breaks international law. Assessments were only taken within Canada. Without local assessments, the tribes have no idea of knowing what the potential threats to the fish in their rivers will even be.

Since the mines reside outside of the United States, and the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act limits how one can sue a foreign government, the SEIDC is petitioning the IACHR for help influencing the Canadian government. Filing a petition of complaint with the IACHR is similar to how one would file a complaint with the United Nations, but with a more regional focus on the Americas. It works conceptually like a lawsuit.

“We didn’t file a lawsuit because we don’t think the laws [in Canada] protect the interests of our clients in Alaska sufficiently,” Pejan said. “There’s no real process for the Southeast Alaska indigenous groups to participate in the decision-making process. That’s why we took it to the Inter-American Commission.”

In November 2017, Alaska officials sent a letter to former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, expressing the same concerns about the development of these large-scale mining operations and their potential catastrophic effects on Alaska.

“We, like this administration, prioritize the promotion and protection of American economic interests, which in this instance could be threatened by B.C. transboundary mining and inadequate financial mechanisms to assure long term management of toxic wastes and redress for damages from potential releases,” the letter said. The letter uses the Tulsequah Chief Mine as an example of the risk and harm that acid mine drainage poses for Alaskans.

They requested that the issue be brought added to the agenda for meetings with the Canadian government.

On Oct. 30, former Gov. Bill Walker penned a letter to the British Columbia government thanking them for their efforts in reviewing and enhancing oversight for the mining industry, but stated that Alaska is still unsatisfied with the financial assurances from the mines that they will clean watersheds to a satisfactory level.

Calls to the Minister of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources in Canada for comment weren’t returned Wednesday.

There are three main requests of the commission: that they make an on-site visit to investigate and confirm threats from the mines, that they hold a hearing to investigate the petition’s claims and that they prepare a report setting forth the facts and laws declaring Canada’s failure to implement adequate protective measures for the watersheds. Suggested actions for the report include suspending activity at the mines until the issue can be resolved and consulting with the tribes to make a plan to protect their resources from acid mine drainage and other pollution that is toxic to fish.

“It’s really hard to isolate any individual project,” said Hanlon in an interview with the Empire. “Our concern really has to do with the cumulative effects in the entire region.”

The 15 different nations represented in the SEITC who submitted the petition come from the Chilkat Indian Village of Klukwan, Douglas Indian Association, Organized Village of Saxman, Craig Tribal Association, Ketchikan Indian Community, Organized Village of Kake, Metlakatla Indian Community, Wrangell Cooperative Association, Sitka Tribe of Alaska, the Klawock Cooperative Association, Petersburg Indian Association, Organized Village of Kasaan, Hydaburg Cooperative Association, Yakutat Tlingit Tribe and Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska. The SEITC was formed in March 2014 as the United Tribal Transboundary Mining Work Group.

The IACHR did not respond for comment Wednesday on how long it will take them to respond to the petition.

Read the full petition on the Earthjustice website.

• Contact reporter Mollie Barnes at 523-2228 or mbarnes@juneauempire.com.