Each year, Alaska Native peoples head out to catch fish and hunt seals as they have for thousands of years. But if current worldwide trends continue, it’s likely they are harvesting more than they think.

Subsistence foods are not exempt from the intrusion of plastics that has swept the globe. Whether you catch a salmon in Sitka Sound or buy a snapper in San Diego, microplastics — pieces of plastic less than 5 mm long — might be part of the package.

Produced when larger plastics (such as bottles, cutlery, bags, packaging, personal care products, and even fleece and spandex) break down, the small plastic particles collect in waterways where they are washed out to sea. Once in the ocean, they are accidentally gulped down by animals ranging from plankton to whales. They also “bioaccumulate,” which means that microplastics animals lower down on the food chain accumulate in the animals that eat them, resulting in higher concentrations of microplastics higher up the food chain.

For people living in Southeast Alaska, the big question is if, and how much, microplastics are showing up in subsistence foods. Up until now, not much work has been done on the issue in the region. But thanks to an EPA Environmental Justice Small Grant award, Sitka Tribe of Alaska (STA) is changing that.

Sitka responds with science

“Plastics aren’t going away anytime soon, and we need to figure out how they’re impacting our environment, and then us, if we’re harvesting subsistence foods,” said Jennifer Hamblen, natural resource specialist for STA. The tribe will spend the next year looking at locally collected shellfish and comparing those results with local supermarket food, such as blue mussels from Argentina or other shellfish from Southeast Asia and the Lower 48.

Hamblen credits Veronica Padula, a PhD student at University of Alaska Anchorage, as the project’s inspiration.

“I invited Veronica to come to STA, meet our staff, and present her research,” Hamblen recalled. Padula’s research on microplastics, sea birds, and the overall harm that plastics cause to the oceans prompted STA to look at ways to collaborate on a pilot project in Sitka.

As a developing field of study, microplastics research does not have a standardized methodology that agencies like STA can use to start studying microplastics.

“New methods are continuously being developed. We had no idea what we were getting into when we applied for this grant,” laughed Hamblen. “So we want to have an EPA-approved protocol for testing microplastics in subsistence foods [that can] be adapted by other agencies, tribes, and organizations to expand upon microplastics research in Southeast Alaska.”

In fact, for Hamblen, gathering data and building a new generation of activists go hand in hand.

“If students are deeply involved in the project and study this enormous challenge facing our world — microplastics — then Sitka, as well as the entire state of Alaska, will have future stewards to look out for our waters and our subsistence resources,” Hamblen said.

Hands on learning

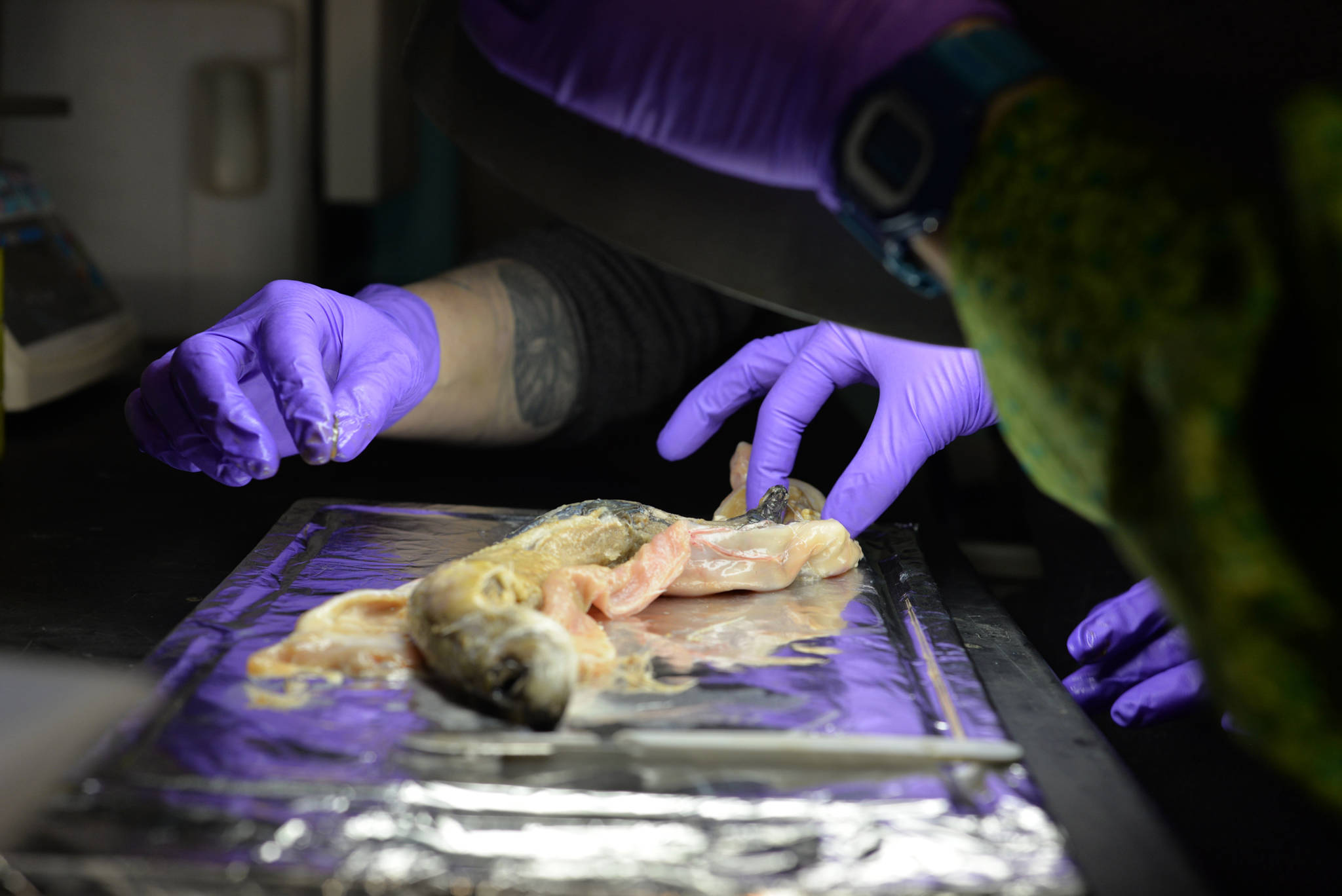

Claire Wilcox, a senior at Mount Edgecumbe High School (MEHS), pressed her knife into the swelled salmon stomach and sliced it lengthwise. She peeled the two halves apart along the incision to reveal the stomach’s contents. Her class was undertaking a microplastics project of its own, also inspired by Padula.

Swinging a magnifying lens over the slimy stomach lining, Wilcox began to scan.

“Hmm, is that something?” she asked, prodding at a small milky fragment.

Squinting through a magnify lens, it can be hard to tell what is partially digested fish bone and what is plastic. The first test to distinguish between organic matter and potential plastics is surprisingly straightforward.

Wilcox dropped the object in question into a beaker of water. If it floated, there was a higher chance that it was plastic. However, three plastics (#1, 3 and 6) will sink and require further tests to figure it out. They also send tissue samples to certified labs for chemical analysis.

“Veronica got students thinking about the marine ecosystem and how contaminants move through the different trophic levels, and they started making connections to their subsistence foods such as fish and marine mammals,” said Chohla Moll, a science teacher at the high school. “So far we have looked into stomachs of sablefish, a variety of species of rockfish and king salmon.”

The studies being conducted by STA and MEHS are still in their early stages. But their focus reflects a global trend in addressing microplastics as a major environmental and health concern, even in remote and relatively pristine corners of the world.

The risks

There are many reasons to be concerned about microplastics appearing in our food. Microplastics bind to heavy metals and toxic chemicals as they pass through the environment—think chemical runoff from waterways and waste treatment plants. In addition to this outside contamination, plastics are typically made with something called “phthalates” — a group of compounds that enhance the color, flexibility and durability of plastic. Inside the human body, these chemicals are carcinogenic and disrupt hormones, increasing the likelihood of birth defects.

What’s more, the sheer mass of plastics in the ocean is reaching unprecedented levels. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation released a study predicting that plastic will outweigh fish in the ocean by 2050.

“I hope that we are giving future community leaders the information, and the empowerment through that information, that they need to speak up when they see something threatening their way of life and their world,” Hamblen said.

• Amelia Greenberg was a freelancer and AmeriCorps volunteer based in Sitka until Jan. 1 of this year, when she moved to Tanzania for a new job.