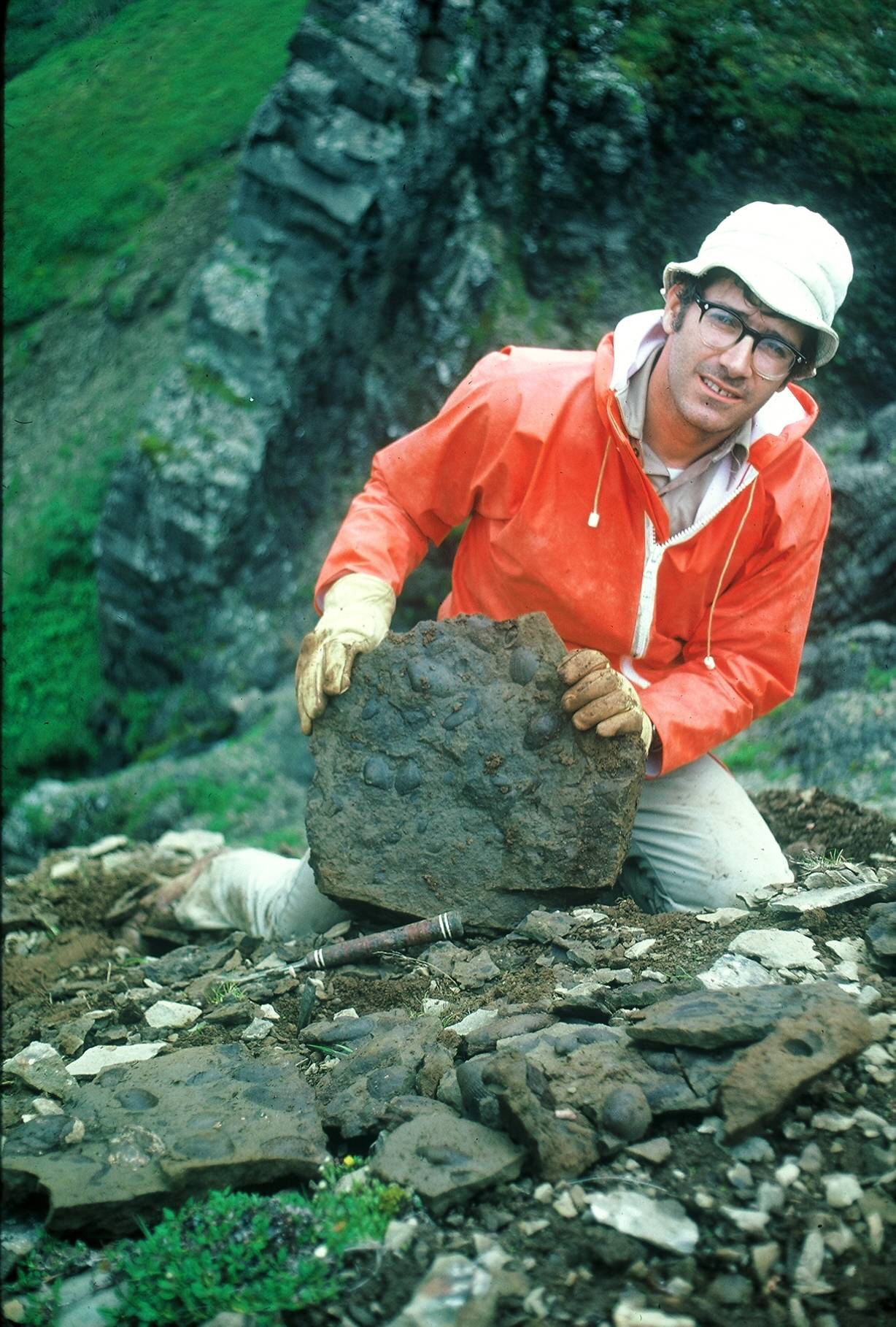

Lou Marincovich’s book “True North: Hunting Fossils Under the Midnight Sun,” published May 15, sheds light on the life of an adventure-seeking paleontologist who, as a young adult just finishing high school, dreamed to live a life of “strong emotion.”

“…and I got it, both the good ones and the bad ones,” Marincovich said. “It put me through quite a few adventures.” Currently he’s a research associate in geology at the California Academy of Sciences, but for 30 years, he combed Alaska in search of seashells. He’s best known for his work that determined the age of the Bering Strait, presenting important implications for climate and animal migration. That discovery landed him on the cover of the scientific journal “Nature,” publishing his article as the feature of the week.

“My specialty was the seashells of the past 65 million years,” he said.

Throughout “True North” Marincovich retells his time in Alaska with enthusiasm having survived dangers such as grizzly bear attacks, landslides, storms and being circled by wolves.

“I was lucky to survive the things I did,” Marincovich said. “As dangerous as it was, that was really living. You’re really alive when there are hazards around; all your senses are heightened… I enjoyed the natural hazards. It’s really thrilling to be out in the bush! I never lost the thrill of leaving California and getting on a plane to Fairbanks or Anchorage and flying into the bush thinking ‘oh boy, this is great!’”

Marincovich said that he never lost the excitement he received from collecting seashells and always maintained those powerful, youthful emotions of discovery.

“Cracking open a rock and seeing a shell for the first time. That is really special… Somehow I landed just the right profession at just the right time,” Marincovich said.

His friends, enraptured by Marincovich’s tales of adventure, attempted to convince him to write a book, but it wasn’t until his wife Karen requested a memoir that, in June of 2008, his work on “True North” began.

“My wife Karen passed away eight months after I’d promised to write my memoirs,” Marincovich said. “I was even more determined to write it after my wife had passed.” The book is now dedicated to Karen. Marincovich attributes the completion of the book to his current girlfriend, Betsy Franco. “My wife Karen got the memoir ball rolling and Betsy kept it going up the slope to the finish,” Marincovich said. “I’ve been blessed to have two transcendent women in my life.”

The book

“I’ve always been interested in crafting words. It’s just fun to play with language. Most scientists are really rigid and it’s all ‘tell, tell, tell’ with them. I discovered in writing a trade book that it is about ‘show, show, show.’ Since I’ve always loved writing I was able to assimilate those kinds of rules,” Marincovich said. “I don’t have any perspective on (this kind of writing) so it took nine years to write these memoirs.”

The first few pages of the book give map references to where his field areas around the North Pacific and Arctic oceans were. There is also a map that specifically locates his field areas in Alaska, and a map of the Cenozoic Era time scale to better understand the age of the fossils Marincovich mentions finding.

This memoir touches on more than only his fossil hunting adventures in Alaska, and begins just after Marincovich had received his bachelor’s degree from the University of California Los Angeles and was considering graduate school. He noticed a summer job announcement for a Geologic Engineering Service on a University of Southern California Geology Department bulletin board that promised $900 a month plus living expenses – just what he needed to succeed in his educational goals.

From 1966 to 1970, he was involved with the worldwide oil exploration community known as the “Oil Patch” in Alaska’s Cook Inlet. His first day as a mudlogger aboard the drill ship Wodeco almost became his last day alive after a solvent leak ushered fumes into the tower he was spending his 12 hour shift. That was only the beginning of the dangers he encountered during his time spent saving money for graduate school.

Marincovich’s determination for continued higher education also brought him to mudlog in West Africa. He spent time working in Dahomey (since renamed Benin) and retells it in his book as a place “where good health goes to die.” Those 375 days 10 hours 18 minutes are moments in his life he says he wishes he could have back.

“I was around a bunch of cutthroats (in Dahomey). I’ve always felt more comfortable around predators than humans. I always had a 12 gauge on me for self-protection.”

In June of 1973, Marincovich received his doctorate and went on to work for Texaco. He had learned all he needed to know about crude oil during his time spent in Cook Inlet and Dahomey and had hopes of collecting fossils instead of working in the petroleum geology field.

“The wilderness had been calling me for decades and I was ready for another adventure,” Marincovich said in his book’s “Driftwood” chapter. It wasn’t until June of 1974 that his childhood dream to collect fossils came true with his being chosen for a field party to the North Slope. Marincovich blames his love for fossils on Roy Chapman Andrews. His mother gave him one of his books called “All About Dinosaurs.”

“That got me started,” Marincovich said. Andrews’ tales of leading expeditions in the Gobi Desert during the 1920s and 1930s in search of dinosaur bones inspired Marincovich.

He wrote in “True North” that, “My soul responded with fervor to Andrews’ stories of wilderness paleontology and this fed my dual drives for adventure and scientific order.”

“I started looking for dinosaurs but all I found was fossil seashells,” Marincovich said. “It was good because dinosaurs are the most dramatic, but they aren’t very useful. What makes (fossils) useful is if they are still living. If you collect a seashell that has a living relative you can relate it and make assumptions from it. A 30 million year old fossil seashell found in Alaska that now lives in California tells you it used to be warmer in Alaska… so understanding seashells are useful for many things.”

Due to the necessity of keeping a journal when collecting and locating fossil mollusks, Marincovich had plenty of noted details to write his memoir. “I remember virtually all of it because I always have a field notebook,” Marincovich said. “So from the weather, to who I was with, to the rocks and fossils, I remember it all.”

Naming a river

Besides his book, he’s also written over 100 scientific articles that have been published. Currently, Marincovich’s retirement project is researching 60 million-year-old fossils in Ellesmere Island, Canada. So far, he’s been there on three separate trips to collect fossils and return back to his home base in California to clean up and study the shells he’s found.

“(There are) very few fossils that age from that part of the world. It can help tell us what the climate was like in the Arctic Ocean 60 million years ago,” Marincovich said. Another exciting moment was when Marincovich discovered two rivers sharing the same name 5-10 miles apart near Port Moller on the Bering Sea. Noticing that someone must have goofed, he took the appropriate measures to rename one of the rivers that he had spent a considerable amount of time at during 1978 and 1999. In February of 2017, the river’s name was officially changed to the Spirit River on Marincovich’s request.

“It was a nice capstone for a long career in the wilderness there,” Marincovich said. “I named it for the sprit of Alaskans, for the people of Alaska. Their spirit is embodied by the phrase ‘the Last Frontier.’ The people who live up there are risk-takers, living in a more challenging place than most others. It’s really satisfying because this river runs right in front of the rock out-crops where I discovered the Bering Strait’s age. I spent a lot of time looking at the river and I never thought I could give it a new name, but when I did I was thrilled. So Spirit River it is!”

Marincovich’s self-published book “True North: Hunting Fossils Under the Midnight Sun” has already had a successful start and has sold out multiple times at one of Marincovich’s local bookstores named Kepler in Menlo Park, California. The book can be found on Amazon where it is available as a paperback; it is also accessible as a Kindle eBook at http://amzn.to/2pm986h.