A massive tsunami-causing landslide in Southeast Alaska on Sunday likely sent more than 100 million cubic meters of debris — the equivalent of 40,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools — into an icy fjord and onto a prominent glacier in one of the largest slides in at least 10 years, according to the Alaska Earthquake Center.

“This is larger than anything in the past decade in Alaska,” Alaska Earthquake Center Director Michael West said in a Tuesday press release. “It’s going to get a lot of attention from scientists.”

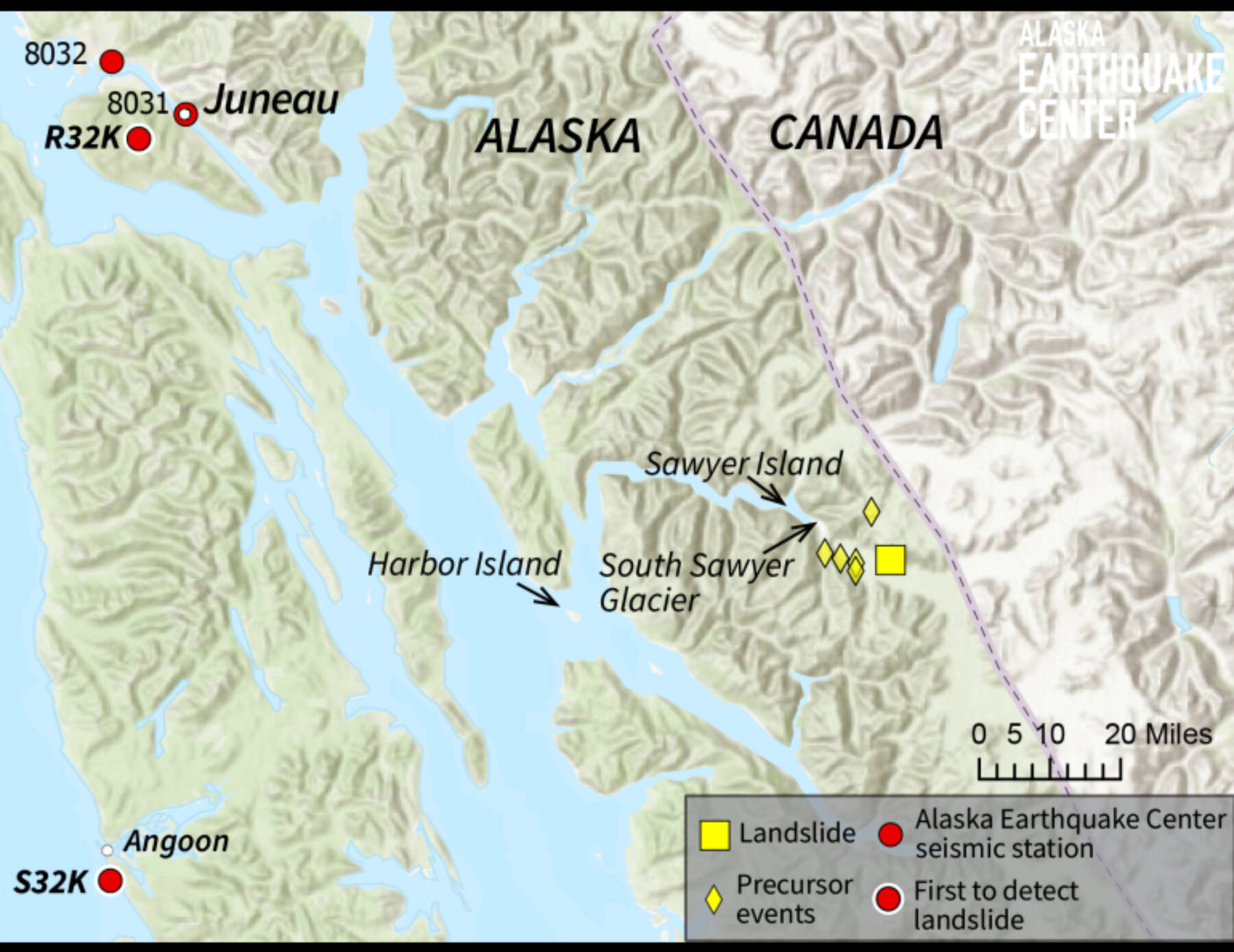

Sunday’s landslide occurred at about 5:30 a.m. at the head of Tracy Arm, a fjord located about 50 miles southeast of Juneau that is traveled regularly by cruise ships and other sightseeing vessels carrying thousands of passengers annually.

A portion of the landslide debris rolled onto Sawyer Glacier, but the rest tumbled into the Arm, creating a trapped tsunami, known as a seiche.

Tsunami waves reached about 100 feet on Sawyer Island, roughly 4 miles from the landslide. On Harbor Island, at the mouth of Tracy Arm and about 36 miles from the landslide, residents reported 20-foot waves.

Heather McFarlin, the center’s seismic data manager, said the landslide’s energy release was approximately equivalent to that from a magnitude 5 earthquake.

The slide was preceded by more than a day of precursor signals recorded by the state’s seismic stations, providing a rare scientific opportunity. West said a possible signal that grows over hours and days before a major event would be the “Holy Grail of hazard monitoring.”

“We were able to produce a rapid location and volume estimate using seismic data as soon as we learned about the event,” said Ezgi Karasözen, a research seismologist at the center who began analyzing the event early Sunday.

Karasözen and West had previously developed a method to detect large landslides remotely within minutes of occurrence and to quickly determine whether slides are close to open water and present a tsunami hazard.

“We now have the ability to quickly analyze and report the size, location and style of landslides,” West said. “That opens the door for building proper warning systems.”

The landslide analysis system worked.

“Our initial location was within 7 kilometers of the ground-truth location, which was confirmed Monday by Coast Guard reconnaissance,” Karasözen said. “It may take weeks or months to get a precise volume, but our early estimate, while uncertain, places this at the upper end of the landslides we’ve detected so far.”

While Sunday’s landslide occurred outside of the center’s landslide detection study area, the recently developed system of detection and characterization was used to provide information about the event quickly.

“There are two different events,” West said of Sunday’s slide and tsunami. “One is a big wave sloshing around in the fjord, and people want to know where that came from. What’s going on?”

Karasözen and West’s method, published in February 2024 in The Seismic Record, can quickly provide answers to those types of questions.

“This event is a strong reminder of why this work matters and how valuable it can be,” Karasözen said. “Once the dust settles, we’ll look at options for incorporating Southeast Alaska into our detection coverage.”