To a graffiti artist, a blank wall represents an opportunity for expression. For a prisoner, it’s the opposite of opportunity – walls are among the many environmental and social structures that confine them physically and psychologically. This describes the conditions of the Lemon Creek Correctional Center in Juneau, Alaska, where my brother Paul McCarthy is an education coordinator.

Several years ago I gave Paul “Walls Notebook,” a book that is a photographic collection of flat urban walls, by Sherwood Forlee. It “contains images of clean New York City walls – from the Lower East Side to the Upper West Side – for you to practice your pieces on before throwing-up the real deal” according to the sherwoodforlee.com website.

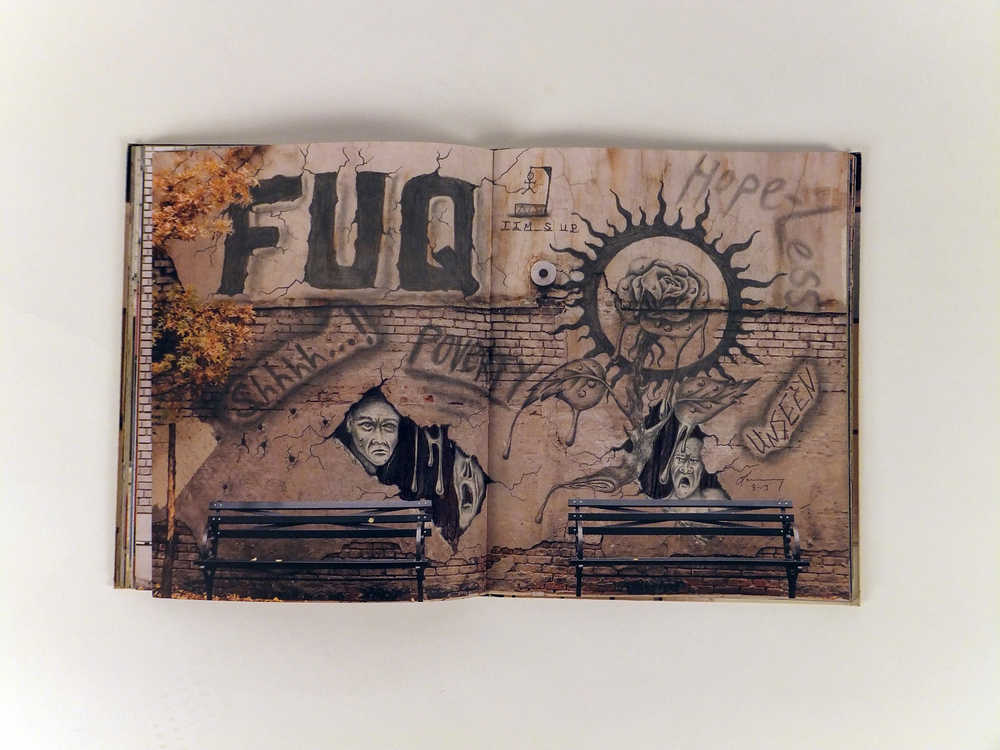

Paul shared “Walls” with the male inmates at Lemon Creek, who enthusiastically drew and lettered into the book using pencil, colored marker and ink, with striking results. A few of the prison artists are truly talented, exhibiting tight craftsmanship, well-proportioned figures and thoughtfully composed scenes.

Recurring images from the prisoners — 80 percent of whom are locked up for felony crimes, some for a very long time — aren’t surprising: buxom women, police violence, tattoo designs, neo-Nazi symbols, drug paraphernalia and gang references are common subjects. Vivid imaginations are at work in many images, although Paul said that some artists copy others’ pictures. The dominant illustration style might be described as a slightly comic gothic surrealism.

Juneau is at the opposite edge of the continent, thousands of miles from New York City. Its equivalent to NYC’s ubiquitous yellow cabs, bustling throngs and sky scrapers are glaciers, wooded mountains, soaring bald eagles and Paul yelling out his kitchen window at black bears to “get the hell out of my raspberries!” Two American cities couldn’t be more different.

Yet, the Alaska-based artists typically respected the photographic reality of New York streets and alleys by obeying conventional graphic rules of depth and demarcation – their drawings were largely confined to the brick portion of a wall, for example, or would honor a newspaper dispenser in the foreground by drawing ‘behind’ it. So even as their art yearned for a certain kind of freedom, the prisoners’ drawings demonstrated an understanding of walls – from printed representations to those built hard of cinder blocks and to those built harder still by the costs of human behavior. They turned the walls into mirrors.

One prisoner, Paul recalls, even stole “Walls” from the learning center library, taking it to another prison for a year or so before it was returned to its proper location. Showing his pride for the art inside, the inmate claimed that “this book belongs to _____” inside the front and back flaps. He is likely still incarcerated, in ironic contradiction to Walls’ back cover blurb: “These textured urban walls provide an interesting backdrop for notes, musings, drawings, doodles and more. Indulge your inner graffiti artist — without the risk of jail time!”

Nine months after writing the first half of this essay, I visited Alaska for the first time since 2004.

I hiked along the Mendenhall Glacier near Juneau and explored its amazing ice caves, sampled local ales at the Alaskan Brewery, and at my brother Paul’s invitation, visited inmates at the Lemon Creek Correctional Center. As I’m a professor of graphic design with an undergraduate degree in drawing, Paul thought that the artistically-inclined prisoners would benefit from a critique session with me.

We entered the grounds’ double security doors, surrounded by razor wire. No cameras, phones or computers were allowed. Once in the building, I was checked with a metal-detecting wand and we were buzzed into the heart of the facility. Paul gave me a quick tour of the learning center and library, largely decorated with maps and nature pictures recycled from calendars, and showed me a stack of photos of inmates beaming with their GEDs.

Seven men were waiting for us in the computer lab, all wearing baggy lemon yellow jumpsuits with “LCCC Prisoner” printed in black capitals on their backs. I guess they ranged in age from twenty-something to more than fifty years old. They all shook my hand and politely introduced themselves.

I began by showing a few slides of my own drawings — I drew once-a-week self portraits for the years 1984, 1996 and 2007 — which were projected from a USB drive via an older computer onto an ad hoc screen made of hastily applied newsprint. Beginning with descriptions of drawing medium and technique, I then discussed the roles of expression and communication, finishing with the notion that self portrait drawing can involve contemplation, a spiritual aspect.

We sat around a table and they shared their art one by one. The first fellow’s work looked like much of the horror-style described above in the Walls book: grotesque, yet cartoony, faces with bloody cuts and diseased mutations. He used color well, especially complimentary relationships. He also used his own skin as a comprehensive canvas, as tattoos covered his arms, neck and the area of his face typically defined by a moustache and goatee.

Most of the drawings were made on 8.5×11 inch white office paper or on the backs of envelopes with graphite, colored pencils or ball point pen. Some of the prisoners brought photographs of their art because they had mailed the originals away. One man showed a magazine that had reproduced a graffiti-like picture he created – clearly it was a point of pride for him. A discussion about copyright and licensing fees for published illustrations followed.

Technical finesse was admired by these artists. Concerns with medium and craftsmanship were more important for most than artistic intention, viewer reception or symbolic meaning. An older prisoner, with a ponytail and a grayish beard that dropped straight down from his lower lip, had faithfully copied a photograph of a grizzly bear in a stream from National Geographic magazine. In pencil – “I had to keep sharpening the lead” – it was hair-for-hair perfect.

He was defensive about not altering the image through any artistic or subject matter interventions. I finally suggested that he use a title or caption to add value to his reproduction. “You mean like ‘Bear in Water’?” he asked. As that’s quite literal, I replied, “how about ‘Bear in Vodka’!” This brought forth some laughs from the others, but he was not swayed.

One prisoner artist, the one whose picture was published, showed potential of commercial success. His illustrations communicated at multiple levels: a woman’s hair began as roses and then morphed into an eagle. He had drawn her to proportion solely from memory and imagination. In another drawing, demonstrating historical awareness, he had elements that referenced nineteenth century Japanese woodblock prints.

Our hour together passed quickly. The prisoners thanked me for my time. One twitchy fellow, who had not brought any drawings to share, asked me if there are any good cardiologists in Minnesota, my home state – he has a heart condition and might need medical help. It occurred to me that the others, in varying degrees of reflection in their own personal mirrors, were helping their hearts through the therapeutic benefit of their art.

—

Read more of this week’s Capital City Weekly:

Canoe likely to be the first 3D-imaged for teaching, models

Moose butchering: Local foods project turns to game

Seaweed farming begins in Southeast