People wait years for permits to raft the Grand Canyon. Michelle Ridgway once visited a much larger canyon in Alaska, one that most people will never hear about.

Zhemchug Canyon, 20 percent longer and deeper than the Grand Canyon, is a t-shaped cut in the sea floor beneath the gray waters of the Bering Sea. On a Greenpeace-sponsored expedition, Ridgway, a marine ecologist and consultant from Juneau, descended into the canyon alone in a tiny submarine.

“I’d been through the Grand Canyon the year before and was expecting a real similar experience,” Ridgway said. “But I was humbled. (Zhemchug Canyon is) enormous.”

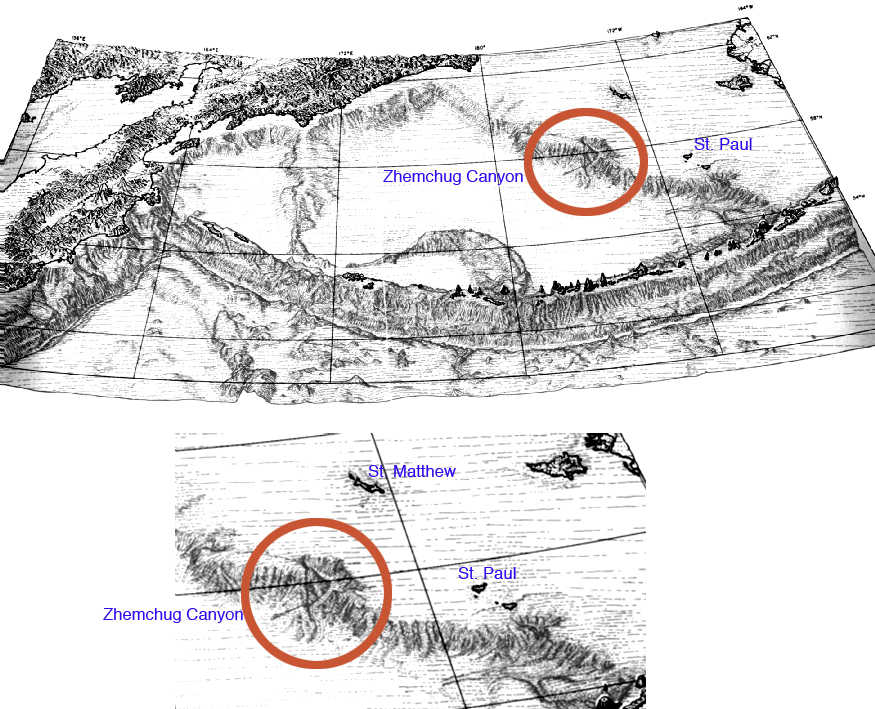

The ancient Yukon River may have contributed to the vastness of Zhemchug Canyon, according to a theory first presented by David Scholl and the late David Hopkins. During the last Ice Age, when more of the world’s oceans were locked up in glaciers, the Yukon flowed a few hundred miles farther southwest. The big river carved the vast gorge that is now Zhemchug Canyon, which lies about 170 miles northwest of St. Paul Island.

Named after a Soviet research ship and a word meaning “pearl,” Zhemchug Canyon cuts into the ocean floor at the western edge of the Continental Shelf, “one of the flattest and smoothest places on the planet,” Dan O’Neill wrote in The Last Giant of Beringia. “Its slope, at no more than three or four inches per mile, is almost unmeasurable.”

From that undersea plain, Zhemchug Canyon plunges more than 8,500 feet into the Aleutian Basin. Michelle Ridgway piloted an eight-foot-long submarine into that abyss.

As she descended and daylight began to fade, Ridgway noticed Dall’s porpoises darting by her tiny craft, which featured a titanium body and pressure-resistant acrylic dome. When she reached 300 feet, the porpoises shot down to her for a final glance before they headed back to the surface. And then she was the only mammal she knew of.

She kept dropping until she reached a bench at 1,757 feet beneath the surface. There, she entered a world of tangerine-colored life forms, including fish, corals, crabs and sponges illuminated by the submarine’s blazing halide beams.

“They ranged from pale gold to a brick red,” she said of the creatures in the dark world of the canyon. “It was very widespread.”

That peculiar color scheme intrigues Ridgway, as does the variety of life in Zhemchug Canyon.

“We didn’t expect such a diversity of sponges and corals,” she said. “And a huge surprise to me is what might be a correction to what we assumed about zooplankton distribution in the water column. The entire water column was teeming with a very dense aggregation of zooplankton.”

A common theory is that the tiny creatures that make up the plankton kingdom hang out nearer to the surface, and the bottom-feeding fish, sponges, and other life forms survive on the leavings of organisms higher up. That might not be true, at least in Zhemchug Canyon.

“It’s rich and living at every depth we examined,” Ridgway said.

Having descended only one-fifth of the canyon’s 8,500 feet, Ridgway hopes she can someday launch an expedition in a submarine equipped to get to the bottom of one of the deepest canyons on the planet. Who knows what unique forms of life await her visit?

“I’d love to go,” she said.

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. He is taking a break for the month of November 2016 to finish a writing project. Fresh columns will reappear starting December 1. This column first appeared in 2007.