Dyea was one of the major towns to grow into prominence as a result of the Klondike gold rush. A small Tlingit village and trading post for many years before the rush with a population around 138 Natives in 1887, it ballooned into a boom town with an estimated population of 5,000 to 8,000 during the winter of 1897-1898. Then a series of events brought about its quick decline. By the time of the 1900 U.S. census only about 250 people remained. In 1902 the post office closed and by 1903, Dyea had become a ghost town, and its few remaining inhabitants supported themselves by farming and selling lumber, windows, and hardware from the many abandoned buildings.

Exactly when Dyea was established is uncertain. Oral history accounts indicated that at one time it was a small permanent village but in the decades before the gold rush it seems to have been a seasonal fishing camp and staging area for trading trips between the coast and the interior. In fact, the name Dayéi means “packing place.” It regained its permanent status probably with the establishment of the Healy & Wilson trading post in the mid 1880s. Various sources suggest a founding date of 1884, 1885 or 1886 for the post, and Healy’s own accounts appear contradictory. John J. Healy, by the way, was a western adventurer par excellence. Before coming to Alaska, he had been a hunter, trapper, soldier, prospector, whiskey trader, editor, guide, Indian scout and sheriff. He was living in Montana Territory when he heard about the early, pre-Klondike Yukon gold strikes; dropping everything, he headed north. In later years, he organized the North American Trading and Transportation Company and was an active supporter of a proposed railroad that would have gone from Canada, north to Alaska, then west to Russia. He died in September 1909.

Edgar Wilson was Healy’s partner and brother-in-law. Not much is known of him. He had a wife named Catherine and a son named Willie. Wilson may have arrived in Dyea a season or two before Healey’s appearance, laying the groundwork for the trading post, which might account for the discrepancy in dates. An early plat map shows the Healy & Wilson trading post consisting of a wood frame main building, which was a combination store and residence, a barn and nearby garden, with the Tlingit village just upriver. The earliest historic photograph of the post seems to have been taken in 1892. Later photographs show that a shed roof wing had been added to the north side of the main structure in the spring of 1897 while a similar shed roof wing was added to the south side of the structure in the late fall of 1897. A sign over the south wing indicates that the trading post was now a “Hotel and Restaurant” with beds and meals at 50 cents each. The post was an important supply and information point for prospectors heading into the Yukon basin before the Klondike gold rush. Local Natives and First Nation peoples gathered there, particularly in the spring, to help prospectors pack their outfits over the Chilkoot Pass.

Beginning in 1880, the number of miners using the Chilkoot Trail increased each year as strikes were made along the Yukon River and especially at Fortymile in 1886 and Circle City in 1893. By 1895, the store had competition from both the Koehler & James partnership and from Joseph Fields, each of whom opened their own short lived trading posts in the village. In 1896, Dyea gained a post office, with Healy & Wilson’s manager Sam Herron as postmaster. A flag pole was then attached to the building and the words “U S Post Office” scrawled on both sides of the front entrance. In the spring of 1897, the news of the Klondike strike had hit the West Coast and the first big wave of stampeders, over 1,000 strong, waded ashore at Dyea and passed northward.

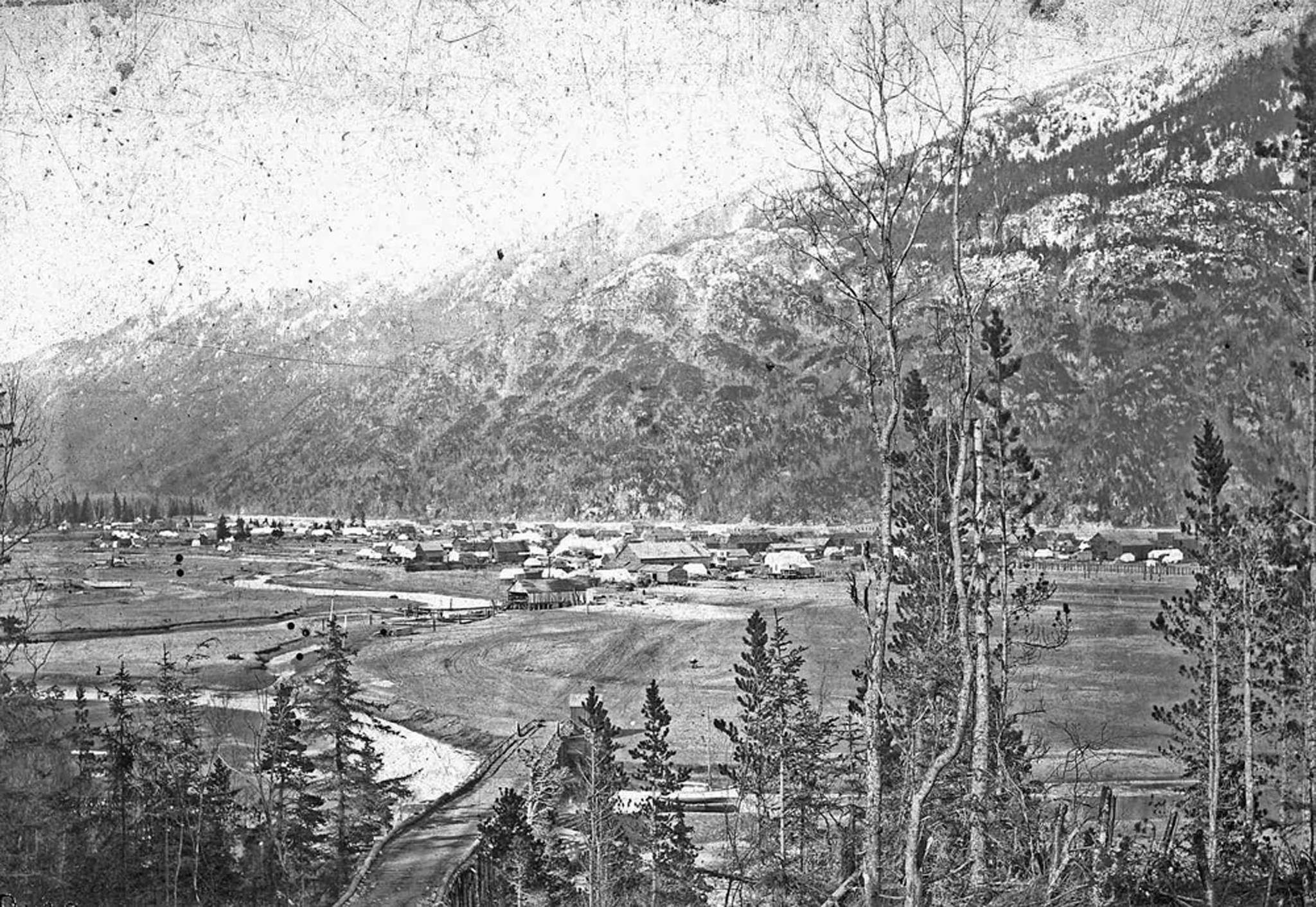

Dyea’s real boom, however, did not begin until the fall of 1897. When word of the returning wealth of the Klondike strike splashed onto the world’s newspapers in mid July 1897, traffic up the Inside Passage grew to a frenzied pace. For months, jammed boatloads of prospectors disembarked here and streamed north over the Chilkoot Pass, but few lingered. As late as September 1897, Dyea was still nothing more than the Healy & Wilson trading post, a few saloons, a Native encampment and a motley assemblage of tents. In October, speculators platted a townsite, but Dyea’s biggest growth did not begin until the Yukon River system started to freeze up and the winter storms slowed traffic on the Chilkoot Trail. The town started declining in population at the end of winter when most of the Stampeders were over the pass.

Gold rush Dyea was large in size and multifaceted in function. The downtown area – about five blocks wide and eight blocks long – was the principal commercial and residential area. It occupied the southern part of the island on which Dyea was situated, and it extended from the west to the east branch of the Taiya River. At the height of its prosperity, the town boasted over 150 businesses, with the large majority of them being restaurants, hotels, supply houses,and saloons. Manufacturing was limited to two breweries. Attorneys, bankers, freighting companies, photographers, steamship and real estate agents were also plentiful. To care for your health, there were drug stores, doctors, a single dentist, two hospitals, and three undertakers. Although the town does not appear to have had any type of formal government, a Chamber of Commerce developed as did a volunteer fire department (but without a building) and a school that ran from May 1898 – June 1900. To connect with the outside world, the town had two weekly newspapers (the Dyea Trail and the Dyea Press) and two telephone companies, one that ran its line up the Chilkoot Trail to Bennett and the other that ran its line to Skagway. There were also two wharfs, many warehouses and freight sorting areas, and a sawmill. The town also had one church, of the Methodist-Episcopalian denomination. Like Skagway, Dyea was gridded out into several north south trending streets – Scow Street, West Street, Broadway, Main Street and River Street. The east-west trending streets were all avenues labeled First Avenue through Twenty-Second Avenue although only the first seven avenues were in the street grid pattern.

North of 7th Avenue was a United States military reservation (Camp Dyea) which blocked most of the north-south trending streets except for Broadway and River Street. Broadway went through the middle of the reservation and appears to have been blocked by the military with a gate. River Street, also called Trail Street or the Old Post Road above 7th Avenue, wound along the banks of the Taiya River past Camp Dyea and up to the Healy & Wilson store, the mid-part of town. Camp Dyea’s northern boundary was the southern boundary of the Healy & Wilson tract. Beyond that, the traveler on River Street encountered the Native Village, locally called “Indian Town” and other boomtown stores scattered along the road. Near the northern end of town, approximately two miles from the high tide line another business center catered to southbound traffic.

Dyea ended at the Kinney Bridge. Here a ferry was used during the early part of the gold rush and by early December 1897 a long log bridge capable of carrying wagons across the Taiya River had been built by promoter L. D. Kinney. The Chilkoot Trail crossed the river at this point and then plunged into the forest as it headed north.

Dyea contained four cemeteries: (1) the first cemetery established chronologically was a small Native Cemetery located along Trail Street in the Native Village. It was for the Natives and is thought to have been mostly washed away by the eroding Taiya River; (2) the second cemetery established was the Dyea Town Cemetery, later also called the Native Cemetery. It was located at the north end of the downtown area, on the block bounded by 6th and 7th Avenues and Broadway and West Streets. It started out primarily for whites but Natives buried after Dyea was abandoned are also found there. It has almost entirely been washed away by the Taiya River; (3) a third burial ground, called the Slide Cemetery, was established northwest of downtown Dyea specifically for the victims of the April 3, 1898 avalanche on the Chilkoot Trail. A few people who died after the avalanche, however, are also buried here; (4) a fourth burial ground may have existed near the Dyea-Klondike Transportation (DKT) Company Wharf site. This was where the U. S. Army was stationed from October 1898 to July 1899 after they moved out of the downtown area. Possibly two or three black soldiers from Company L, 24th Infantry were buried there. Finally, a fifth cemetery was created by the National Park Service in 1978 when the Service moved some graves located in the Dyea Town Cemetery to a new location near the Slide Cemetery after they were threatened by river erosion.

West of River Street and immediately north of downtown was Camp Dyea, or Camp Taiya. U.S. Army troops first arrived there around March 1, 1898 and soon their tents were scattered across a large, open field located just north of 7th Avenue, west of River Street and south of the Healy & Wilson trading post. Their tipi style Sibley tents and other canvas wall tents were located both east and west of Broadway, a rude track which roughly bisected the camp. The facility also boasted a rough wood fence surround the camp, a crude parade ground, pack animals and tons of feed, which had been brought north as part of the much ballyhooed Klondike Relief Expedition. Camp Dyea was a receiving point for the expedition and troops involved in the operation were stationed at Dyea for several months. But the expedition was a disaster. Out of 538 reindeer originally acquired from Norway to feed the starving miners in Dawson, only 114 reindeer arrived in Circle City a year too late. Supplies never got beyond the depot at Dyea and they were eventually auctioned off.

The sole purpose of the troops in Dyea was to show the flag and to prevent mob rule. The army did not intend to stay long, but the frontier boomtown atmosphere kept them busy. They were called out on numerous occasions in 1898 and 1899, most notably after the Palm Sunday avalanche along the Chilkoot Trail and the Soapy Smith Frank Reid gunfight on the Juneau Wharf in Skagway.

When the troops arrived in Dyea, they paid little attention to the site where they established their camp. But drainage problems existed at the site, the nearest potable water was over a half mile away and the camp was not directly accessible by water. Therefore, the troops sought out another location. Three miles south, along the west side of the Taiya Inlet, the army secured the DKT Company wharf site and in October 1898, they moved there.

Dyea competed on fairly even terms with Skagway through the winter of 1897 1898, but with the coming of spring, Dyea began to lose its competitive edge. On April 3, 1898, a massive snow slide along the Chilkoot Trail north of Sheep Camp killed over 70 people. It brought worldwide negative publicity and some northbound travelers steered away from Dyea. The coming of spring and the opening of the Yukon River brought a mass exodus from the town as the expectant Klondikers left for Dawson and another hoped for wave of Stampeders failed to materialize. The construction of the White Pass & Yukon Route railroad, which began in Skagway in May 1898, funneled most of the new Stampeders to Skagway. Freight destined for the aerial tramways of the Chilkoot Railroad & Transport Company continued to pour through Dyea, but few passengers filed into town. Finally, the replacement of the Klondike gold rush with the Spanish American war in the nation’s headlines, spelled Dyea’s doom. Reeling under the combined effects of this bad news, Dyea’s role as a gold rush boom town quickly faded.

In late 1898, the onslaught of winter snows slowed and then halted tramway operations for a time. By the spring of 1899, portions of the Long Wharf were no longer usable. In late July 1899 the U.S. Army was burned out of their camp at the DKT Company wharf site by a forest fire and moved to Skagway never to return. By the summer of 1899, the aerial tramways over the Chilkoot Trail were purchased by the White Pass & Yukon Route railroad and operations came to a halt. Most of the tramway apparatus was removed in early 1900 and the Chilkoot Trail ceased being a transportation corridor after hundreds of years and Dyea’s reason for being vanished.

After 1900, the population of Dyea continued to slump. Although about 250 people lived there in March 1900, an informal tally in the spring of 1901 showed only 71 people with any interest in the town. Those who remained hoped to benefit from various railroad or townsite schemes that were being promoted at the time, but when the schemes failed to bear fruit the inhabitants drifted away. The post office closed in June 1902, and by 1903 less than a half dozen people occupied the remains of the old townsite.

Once people left town, the valley began to show opportunities as a farming area. Four operators there raised vegetables for the Skagway market in 1900, and a few continued intermittently for another 40 years. Joseph Waughn, William Matthews, Ernest Richter, Mary Hart, Emil Klatt and William Maksym all claimed land in Dyea before 1915. All relinquished their land to or were bought out by Harriet Pullen, the well known Skagway hotel owner, who established a truck garden and dairy farm there. Meanwhile, the remains of the old townsite slowly disappeared. A few of the owners dismantled their buildings and took them elsewhere. Emil Klatt, who farmed in the valley for years after the gold rush, burned or disassembled many of the old buildings gaining some money by selling off lumber and hardware and expanding his farm. Fires destroyed some buildings including the landmark Healy & Wilson trading post (in January 1921) and vandalism ruined a few others. Time and the elements wore down many of the other old buildings and a shift in the path of the Taiya River has undermined over half of the downtown area beginning in the 1910s. Some of the buildings from the town remained until after World War II but more floods in the mid 1940s and early 1950s destroyed most structures which were left standing. It appears that the only buildings for which any substantial evidence is left were re used by farmers or other homesteaders after the gold rush. Today there are no standing structures in Dyea with the exception of a single wall, the false front of the A. M Gregg Real Estate office. Many ruins still remain at the old townsite but identification of the ruins is difficult and many questions still remain. The town is now and has been for some time, a major archaeological site. In February 1978, the National Park Service bought much of the old townsite of Dyea and have recently built new trails following the original street grid and installed new wayside exhibits on the old gold rush town.

• This report was originally researched and written by Frank Norris, as part of a Historic Structure Report on Dyea and the Chilkoot Trail that was never published. The original report has been edited and revised by Karl Gurcke, a Skagway historian who works at the National Park Service, to include additional material from Frank Norris’ 1996 report on the Legacy of the Gold Rush: An Administrative History of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Thomas Thornton’s 2004 report on the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, M. J. Kirchhoff’s 2012 book entitled Dyea, Alaska, The Rise and Fall of a Klondike Gold Rush Town and Samson Ferreira draft 2013 Cultural Landscape Report for the Dyea historic townsite. An earlier version of this article was read over the air on KHNS, the Haines public radio station.