Polarizing Petition: Hundreds call for statue’s removal

Published 4:00 am Saturday, June 20, 2020

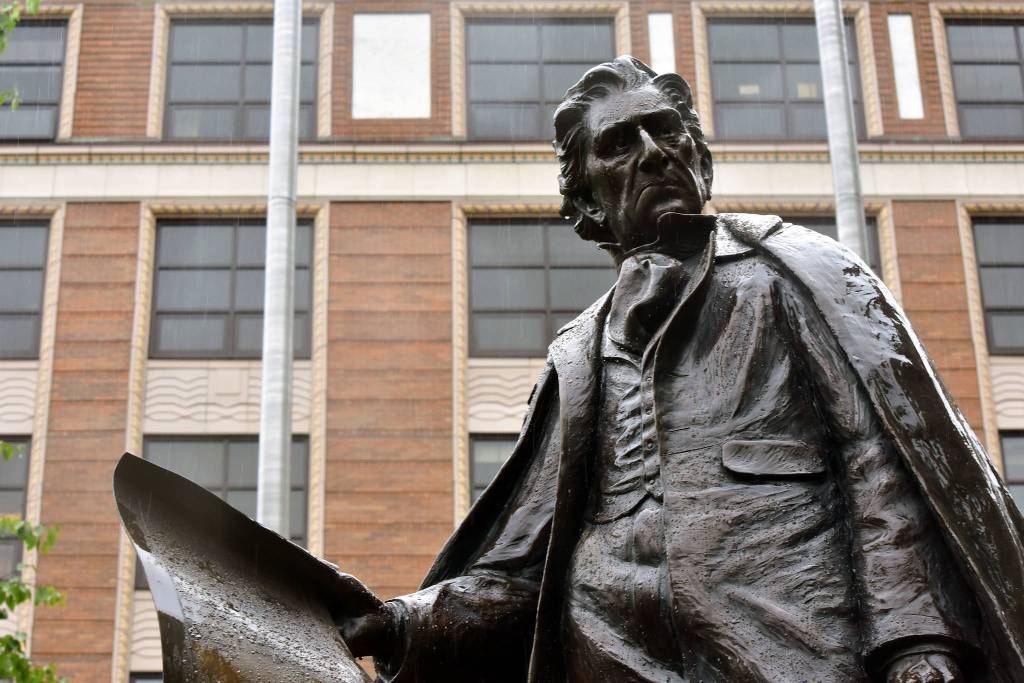

A petition has been filed calling for the removal of the statue of William H. Seward from Dimond Courthouse Plaza across from the Alaska State Capitol.

In the wake of the death George Floyd, a black man who died in Minneapolis police custody after an officer pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck, statues of historical figures have been torn down, vandalized or peaceably removed as protesters call for a re-examination of those figures’ legacies and reconsideration of what kind of people are memorialized in the public square.

[Seward Statue fully funded, days away from installation]

Last week Juneau resident Jennifer LaRoe started a Change.org petition to remove the statue of Seward, the Secretary of State who organized the purchase of the Alaska Territory, from a plaza downtown.

The statue is owned by the State of Alaska, which also owns Dimond Courthouse Plaza where the statue is located, according to City and Borough of Juneau data, so the state would be responsible for the statue’s removal. The petition was officially addressed to Juneau’s Sen. Jesse Kiehl and Rep. Sara Hannan, both Democrats, whose districts cover downtown Juneau where the statue is located.

Kiehl on Friday declined to comment until he was more familiar with the petition. Hannan was outside of cellphone coverage, according to her staff.

As of Friday afternoon, more than 1,300 people had signed the petition. However, being an online petition, signers do not have to be Alaska residents.

In an interview Thursday, LaRoe said the protests around Floyd’s death and the current re-examination of historical figures made now the perfect time to discuss what Seward represents to Alaska.

“This is the right time to discuss and look at what our society views as OK and help people understand other perspectives,” LaRoe said.

The man vs. the symbol

The issue is not with Seward himself, LaRoe said.

She acknowledged Seward’s role as an abolitionist in the Lincoln administration and aid to Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. However, she does take issue with what the statue of Seward represents.

“My issue isn’t really with Seward the person, I don’t think that relates to the issue here,” LaRoe said, noting the statue showed Seward holding the 1867 Treaty of Cession which authorized the sale of Alaska from the Russian Empire.

“Depicting the purchase of Alaska, which represents the disenfranchisement of indigenous peoples,” isn’t something that should be memorialized in a statue across from the Alaska State Capitol, she said.

“(Alaska Natives) didn’t’ sell their land to the U.S., and that wrong has never been corrected,” LaRoe said.

LaRoe said she questioned why the statue was even erected in the first place as it reflected not only the disenfranchisement of Alaska Natives but was yet another symbol of white, patriarchal authority.

“I don’t know much of (Seward’s) character and am not concerned,” she said. “It’s more about in this current day and age, putting up a statue of something that is harmful to the first people of Alaska.”

LaRoe said she’d like to see the statue removed and replaced with someone who doesn’t offend certain segments of the population, and suggested Alaska civil rights icon Elizabeth Peratrovich as an alternative.

In a letter sent to the Empire, Sealaska Heritage Institute President Rosita Worl said removing the statue would be consistent with the long-held views of Southeast Alaska Natives.

“Seward embodied Manifest Destiny,” Worl wrote. “His imperialistic vision was founded on white supremacy. The history endured by Native Americans in the Lower 48 states repeated itself in Alaska with the suppression of Native cultures, languages and spirituality and the expropriation of our land and natural resources.”

Seward was certainly an imperfect figure, said Dave Rubin, the artist who crafted the statue with his sister, Judith, but his legacy in Alaska is important.

“I encourage the discussion,” Rubin said of removing the statue. “I’m an artist, that’s my art. I’m very proud of it. It is a complicated legacy. Seward was the man who put the Emancipation Proclamation into legislation, his home was the last stop on the Underground Railroad.”

[Preserving a scar: Seward statue debate exposes differing views on history]

When the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1864, Seward was Lincoln’s Secretary of State and contributed language to early drafts of the document, according to the Library of Congress. Documents from the William Henry Seward Papers at the University of Rochester Library show Seward sold a plot of land to Harriet Tubman, founder of the Underground Railroad.

“I really think the discussion should come down to human behavior. There’s no race on this planet that escapes the blame for behaving that way,” Rubin said, referring to past atrocities in human history.

He said he doesn’t want to see the statue destroyed, but he hoped it would be preserved in some way even if it were moved from its current location.

“Not only because of their historical value but also because it’s a work of art. I know it symbolizes something, tearing it down is a symbolic act as well,” he said.

Tony Tengs is a Juneau resident who’s apprehensive about seeing the statue removed.

He, like Rubin, admits that Seward was an imperfect person, but Tengs doesn’t want to see Seward compared to Confederate generals who fought for slavery.

“The statue installation has education value, it speaks to all Alaska Native tribes affected by Seward,” Tengs said. “In the Black Lives Matter collective history, he would probably be honored for his work with Harriet Tubman.”

Tengs said he identified with Seward because they both have scars on their bodies, and appreciated that aspect was incorporated into the statue.

[Seward statue takes place in front of Capitol]

“I know that many people have been scarred under the U.S. occupation of this land. Maybe there can be further commentaries surrounding this,” Tengs said, suggesting additions to the plaza highlighting other narratives.

Tengs said he understood the complexities of Seward’s legacy, but didn’t want to see his legacy passed over in a rush to action.

“I know it’s very fashionable, it happens to be the closest statue of a white man in this BLM rage,” Tengs said.

He supports Black Lives Matter, he said, but was concerned when he saw Facebook posts concerning the statue linking to videos showing how to tear them down.

Both Tengs and Rubin said they would not oppose having the statue moved to a museum, and option which LaRoe tentatively relatively endorsed.

The past and the future

Objections to the statue were raised even during the planning phases.

In April 2017, a few months before the statue was unveiled, a shame totem was erected in the village of Saxman, a recreation of a pole from the 1880’s ridiculing Seward for failing to repay gifts, according to an article in the Alaska Historical Society.

The statue was installed in 2017 after three years of fund-raising by a local planning committee to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Cession. The statue cost roughly $250,000 most of which came from grants and donations, the Empire reported at the time.

The largest donation, $28,000, came from the Alaska Historical Commission, which is part of the Department of Natural Resources. The City and Borough of Juneau donated $25,000 from its Parks and Recreation Department budget, the Empire reported.

Under previous ownership the Juneau Empire supported the statue and is listed as one of its major sponsors. The Empire was owned by Morris Communications at the time and published an editorial in support of its installation and context for Seward’s complicated legacy.

Josh O’Connor, president of Sound Publishing, which currently owns the Empire, declined to comment citing a lack of background information.

Worl said she expressed her concerns to the state in 2016 “to no avail,” and suggested that if the state were to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Cession, it should also adopt the Canadian model for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“For myself, I am reminded on a near-daily basis of Seward’s history and the symbols he represents with the naming of Seward Street running in front of the Walter Soboleff Building,” Worl wrote. “Can we not hold up our heroes and name our streets after the likes of Walter Soboleff? Can we not join in with the rest of the country to engage in respectful dialog to address the past wounds with which we still live?”

• Contact reporter Peter Segall at psegall@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @SegallJnoEmpire.