From space, the Nogahabara Dunes are a splotch of blond sand about six miles in diameter surrounded by green boreal forest. Located west of the Koyukuk River, the dunes are the site of an uncommon discovery.

In 2001, biologists for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service were walking the dunes when they noticed the sand was infused with black rocks. Looking closer, they saw the rocks were obsidian, attractive pieces of black volcanic glass.

Before the days of metal tools, prehistoric hunters worked obsidian into points sharp enough to penetrate animal hides. Many a bison and caribou fell to spears and arrows tipped with obsidian, which can be worked sharper than a scalpel.

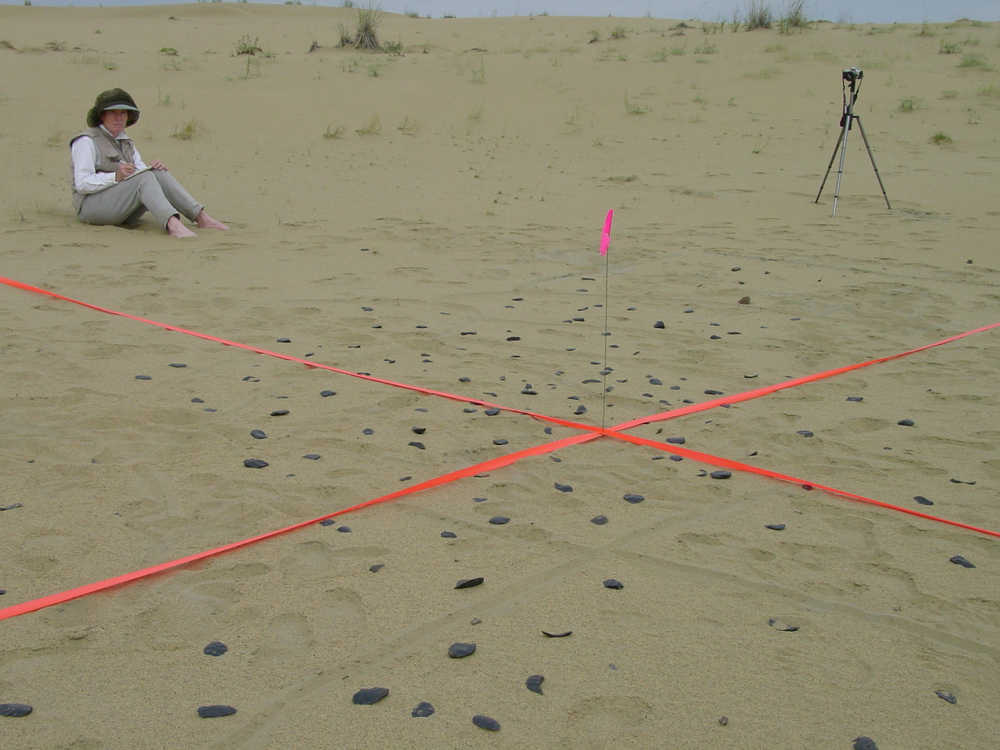

A few years after the find in the Nogahabara Dunes, archaeologists Dan Odess and Jeff Rasic landed in float plane on a lake at the edge of the sand. They hiked to the site described by the biologists and saw an accumulation of obsidian pieces like nothing they had ever seen.

Within an area the size of a large cabin, the scientists found 267 obsidian tools. Together, the pieces weighed 13.5 pounds.

Rasic works for the National Park Service and knows a lot about obsidian and other stone tools. The dune site is special, he said. Obsidian points are often broken or worn, but the Nogahabara featured points that were almost perfect and others in various stages of being worked to that end.

“It’s dominated by whole useful tools and some at different stages of manufacture and use,” he said. “It’s like a user’s guide to how to make these stone tools.”

That scattering of sharp rocks in the sand, left there perhaps 12,000 years ago, inspired Rasic and Odess to write a paper. In it, they envisioned a hunter or group of hunters leaving behind a tool kit. A common interpretation of found stone tools is that hunters lost them or discarded them.

“If you find a pile of Swiss Army knives, you wouldn’t think someone dropped them there,” Rasic said. “Maybe somebody stashed their outfit there and never came back to get it.”

The site, which is now a pile of sand, is not a great lookout point. Bones and other artifacts found at the site make Rasic think people occupied it for a brief amount of time.

“The simplest explanation is that this spot was visited only once, perhaps for days or weeks, but not repeatedly over years or decades,” Rasic once wrote.

Most of the obsidian toolkit from the Nogahabara Dunes is in a few drawers at the University of Alaska Museum of the North. Some of the best points, ones you could attach with sinew to a wooden shaft today and fling at a caribou, are upstairs in a public viewing gallery.

Those pieces are a stunning example of a material found at archeological sites across Alaska, the Yukon, British Columbia and Siberia. In a quest to identify obsidian tools found at Alaska sites, Rasic has traveled to museums around the world with a hand-held X-ray device that allows him to pinpoint the source of the glassy black rock.

Many ancient volcanic deposits throughout the state have left behind blobs of obsidian. Ancient hunters (and Rasic) had the ability to chip the rocks into tools. By far the most common source of Alaska obsidian is known as Batza Tena, about 95 miles from the Nogahabara Dunes. The tools from the dunes have the same chemical fingerprint as the Batza Tena rocks.

Batza Tena is a flat-topped ridge between the valleys of Indian and Little Indian rivers, about 12 miles south of the village of Hughes. Black rocks are sprinkled on the surface and are exposed in the cobbles of nearby water-ways. The site is now quiet wilderness that has probably not changed much since people were picking up black rocks there thousands of years ago.

I injected a few errors into last week’s column on dancing wires. Neal Davis started his career at the Geophysical Institute in the 1950s. And this column, the Alaska Science Forum, evolved from a suggestion to Davis from historian Claus-M Naske.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.