Threads of the Tongass: Building a sustainable future

Published 9:30 pm Thursday, July 17, 2025

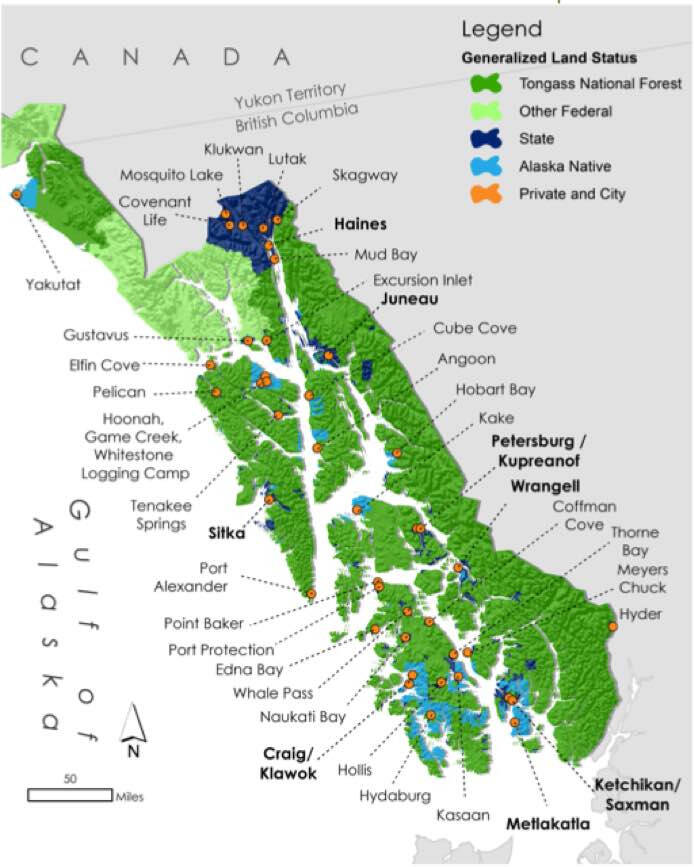

“Threads of the Tongass” is a series of stories that explore how lives in Southeast Alaska are interwoven with the Tongass National Forest during a time of political, cultural and environmental change. This final article features Southeast Alaska perspectives that take a holistic approach to federal, state, city, and tribal land management.

The days of clear-cutting the Tongass National Forest are over, with little chance of reviving the past. The Alaska Forest Association, tribal members, and environmentalists say a new future must be charted.

Since the Clinton administration implemented the Roadless Rule in 2001, construction of new roads in wild areas of most national forests has been blocked. With no more roads being built and few companies willing to barge out the wood, it is difficult to imagine the return of mass logging.

Timber operators expected to harvest 46 million board feet per year, a mix of young and old-growth, based on the 2016 Tongass Land and Resource Management plan. Viking Lumber Company in Klawock and Alcan Timber in Ketchikan acknowledge the time needed to transition to young-growth harvesting.

Meanwhile, tribal and environmental organizations in Southeast Alaska are focusing on repairing the largest forest in the nation — home to 71,077 people and more than 400 species.

Bob Girt recently retired from Sealaska Timber Corporation after 40 years. To build a path forward, he said, he had to admit he was wrong.

With the mindset of supporting his family, he first came to Alaska from Oregon in the 1980s to work as a liaison forester at a logging camp on Prince of Wales Island.

“I’m going to do what I was trained to do,” Girt said. “I’m going to lay out roads. I’m gonna put harvest boundaries around trees. I’m gonna maximize revenue for the company that I work for.”

After the company went into bankruptcy, Girt was hired as a field engineer for Sealaska Timber in 1985. Even then, he said, his mindset was the same.

“But I must say that I didn’t give much thought, if any — I’m ashamed to admit this — to the people and the communities around which this was happening,” he said.

Girt continued to lay out roads, design bridges and bridge crossings, and establish harvest boundaries for mostly clear-cut areas until 1989. He was then promoted to manager of the engineering department, where he assisted in planning the timber harvests for Hoonah, Kake, Dall Island, and Prince of Wales. In 1995, Girt became operations manager, negotiating contracts with road builders, logging companies, and shipping companies.

During his 40-year career with Sealaska Timber, he held various roles, earning promotions that involved designing roads on Prince of Wales Island and Dall Island.

In late 2016, Girt said he found his true calling — developing workforce development programs. By 2017, his position as chief engineer included managing environmental permits. That year, he and others started the Alaska Youth Stewards Program.

“In my entire career with Sealaska, these last several years have been the most enjoyable, the most rewarding,” Girt said.

Youth steward crews are now in their eighth season and based out of Angoon, Hoonah, Kake, and on Prince of Wales Island. The crews work on trail construction and maintenance, stream restoration and ocean monitoring, traditional food harvests, and community garden development.

Through his work with youth, Girt realized the Tongass National Forest is sacred to tribal communities. He said he has also come to appreciate its value — after all, it is his home too.

“It’s such a special place, and so that has impacted my thinking as well,” Girt said. “My care, genuine care and concern for the land and for what happened on it is so much deeper, exponentially than what it was even 20 years ago.”

The Sustainable Southeast Partnership comprises international, regional, and community-based organizations, tribal governments, land managers, entrepreneurs, Native corporations, experts in food sovereignty, land management, local business, energy systems, and other related fields. Participating members engage either as individuals or as representatives of a partner organization. Alaska Youth Stewards are included in the partnership.

In the last decade, Girt said his perspective shifted. At a Sustainable Southeast Partnership spring retreat in Sitka this year, he apologized for his role in clear-cutting the forest.

“I’ve cried in front of people and said, ‘You know what, I’m sorry that I didn’t think about these things,” he said. “I’ve had a hand in some of the stuff that’s happened around your communities, and without giving it any thought. That has been a healing journey for me.”

Last year, Girt’s students constructed a 20-foot bridge along the Klawock River, a crucial salmon spawning habitat. The bridge connected two portions of the trail on land owned by the Klawock Heenya Corporation. Girt used his forest engineering experience to help — bridging the gap between his past and the restoration model he has designed for the future.

“These students can look back and say, ‘I helped build that. I was a contributor,’ ” he said.

The youth are shaping the forest today, he said.

“Your voice matters,” Girt told them. “Don’t be afraid. Don’t be afraid to speak, but also be teachable. Be humble and conduct your life with integrity. Be purposefully passionate and care about the land.”

‘Be teachable’

In Sitka, high school students are being taught how to build a learning pavilion using young-growth timber from the Tongass. This summer, the lumber was transported by flatbed truck on a state ferry from Petersburg to Sitka.

The Sitka Conservation Society has collaborated with Pacific High School students for several years on a school garden. The students work in a greenhouse and outdoor beds. They envisioned a shelter as a place where they could be protected from the rain while growing their garden. Shelter construction will begin in August, when school starts.

The learning pavilion connects locally grown food with locally sourced building materials.

“The reason we’re doing the school garden is both as an investment in health and nutrition, workforce development, to teach these kids to just love to be outdoors – working hard, shoveling dirt, pulling vegetables,” said Andrew Thoms, executive director of the conservation society.

He said mental health skills come along with hard work and seeing a job well done.

Sitka Conservation Society members visited Alaska Timber and Truss in Petersburg, which harvests 50-year-old tree stands. After learning about the mill operations, the organization purchased a kit that included massive 12 x 12 and 8 x 12 beams for the school’s outdoor pavilion.

“For us at the Conservation Society, doing things in that way makes a lot more sense and is a lot more sustainable than loading up all of our logs onto a ship and sending them to China,” Thoms said.

The conservation society was formed in 1967 when pulp mill excesses were “becoming clear to a lot of people here in Sitka, and areas were being cut that should have never been harvested.”

The Pacific High School project in Sitka aligns with the society’s mission to develop sustainable communities, drawing inspiration from Bob Girt’s integration of youth in the workforce.

Historically, Thoms said, the organization has been focused on protecting the Tongass by keeping large areas of impact habitat protected to maintain functional ecosystems.

“But that doesn’t mean that there’s no timber harvesting on the Tongass,” Thoms said. “We just have to do it in the right way. Fifty-five years later, the work we’re doing is trying to bring those forestry practices to Tongass management to figure out, ‘How do we do forestry right in Southeast Alaska, how do we figure out these are the areas that we need to protect and not touch, and these are the areas where we can do forestry and timber harvest and use those products?’”

Thoms said repealing the Roadless Rule will create conflict and distraction, making it more difficult for organizations to bring their shared vision for the timber sector to fruition.

“For us, the Roadless Rule is a big bait and switch,” he said. “The cost of doing only new road building in roadless areas is going to be so prohibitive that roads aren’t going to be built. And the actual cost of logging in those areas and getting a tree out of the woods, it won’t pay for itself. So it’s a huge distraction that’s taken energy and time away from doing the kind of project that we need to do to move things ahead.”

‘Care about the land’

On Prince of Wales Island, youth are finding alternatives to commercial clear-cut logging in Klawock and beyond.

Quinn Aboudara is the Prince of Wales coordinator for the Klawock Indigenous Forest Stewards in Shaan Seet Incorporated (Village Corp in Craig). He said each organization within the forest partnership can undertake individual projects, but they share a common vision.

“As a partnership, we focus mainly on watershed assessment, climate change, and adaptability, wildlife restoration, thinning projects, and habitat improvement projects in stream restoration,” Aboudara said.

This summer, the first in-stream restoration project of the year began, involving Shaan Seet, Sealaska Incorporated, and the Alaska Youth Stewards Program. Aboudara said a foundation of the forest partnership is engaging with the Alaska Youth Stewards, and they have worked closely with Bob Girt.

“We have this shared vision of raising local generations into natural resources management and stewardship,” Aboudara said. “It goes beyond management. It really is reconnecting Indigenous people with Indigenous places and Indigenous management practices and rights.”

He said the mission of the forest partnership is to empower future generations to have the skills and confidence to make decisions. The Tongass includes U.S. Forest Service land, as well as land allotted through the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. Aboudara said it is essential that youth lead not only on lands managed by Native corporations, but also on federal and state-managed lands surrounding their communities.

On Prince of Wales Island, only a small portion of the remaining old-growth reserves are viable for timber, Aboudara said.

“While we do support a timber industry…what’s it going to take for people to realize the old-growth has to be preserved because it’s the last of it?” Aboudara asked. “What we’re recommending is actually transitioning to second-growth forests because so much was harvested in such a short amount of time.”

He said he would like to see a localized lumber industry, where timber is processed and sold locally, especially to develop housing opportunities. Aboudara said the local second-growth forests already have a substantial amount of infrastructure in place to support accessibility.

“We are trying to bring second-growth forests to a stage that is more like old-growth conditions to create that biodiversity within our second-growth forest that could support additional biological biodiversity, animals,” he said. “They are complex ecosystems from the top of the tree down to the deepest of its roots.”

Prince of Wales Island has been managed for timber for almost 100 years. Aboudara said he grew up seeing the widespread industrial timber harvest of the 1980s and 1990s.

“Now, there are no benefits to reap from those past practices,” Aboudara said. “Our salmon populations have declined — our deer populations have declined. Our gathering opportunities have declined. So it’s important for us to do the work now, to begin the restoration process, so that our children and great-grandchildren and so on, behind us, are the ones who may have the opportunity to reap the benefits of the work that we do today.”

Bob Girt retired in May. He said that old-growth timber harvests will never be the same, even if the Forest Service and one or more of the Native corporations, including Sealaska, transition to second-growth harvest.

Girt remains passionate and involved with the Alaska Youth Stewards.

“Even though some of the students, they’ve graduated high school, they went on to college — we’ve stayed connected and I’m just deeply proud of them,” he said.

• Contact Jasz Garrett at jasz.garrett@juneauempire.com or (907) 723-9356.