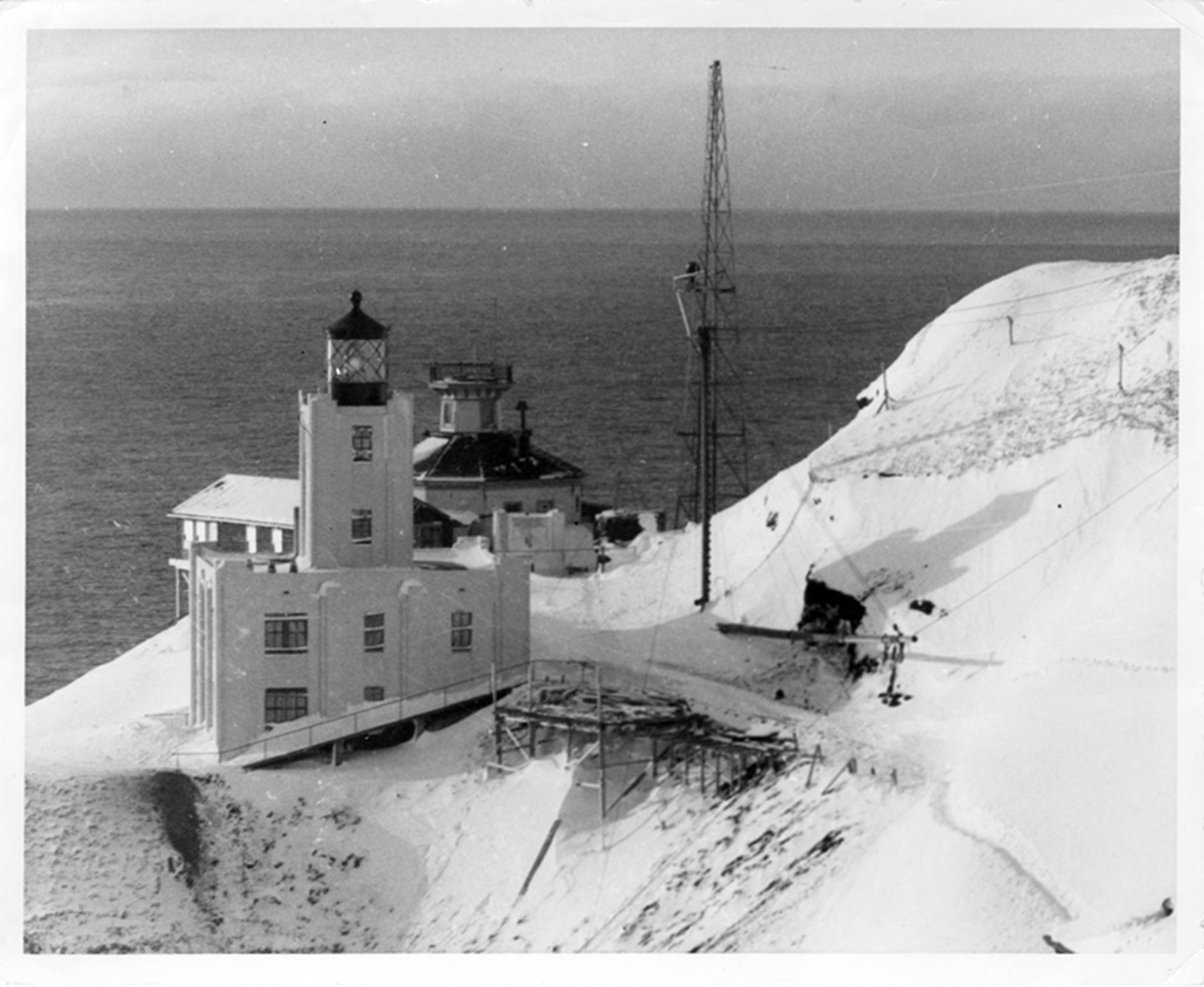

In spring of 1946, five men stationed at the Scotch Cap lighthouse had reasons to be happy. World War II was over. They had survived. Their lonely Coast Guard assignment on Unimak Island would be over in a few months.

But the lighthouse tenders would never return to their homes in the Lower 48. In the early morning of April 1, the earth ruptured deep within the Aleutian Trench 90 miles south. An immense block of ocean floor rose, tipping salt water across the North Pacific.

The earthquake was giant, at least magnitude 8.1. The tsunami that resulted killed 159 people in Hawaii, drowned a swimmer in Santa Cruz, banged up fishing boats in Chile and wrecked a hut on Antarctica. The curve of the Aleutians protected much of Alaska, but the five men at Scotch Cap had no chance.

A 130-foot wave struck the lighthouse at 2:18 a.m., leaving nothing but the foundation of the reinforced concrete structure. Though scientists long thought the wave was due to the earthquake rupture, John Miller of the USGS in Denver recently showed a mountain of rocks on the sea floor that appears to be from a massive underwater landslide. That slide might have created the giant wave that hit the lighthouse.

The story of Coast Guardsmen Anthony Petit, Jack Colvin, Dewey Dykstra, Leonard Pickering and Paul Ness is 73 years old and is spotty. Enduring online is a memo to his superiors written by Coast Guard electrician Hoban Sanford, who was stationed on Unimak to maintain a radio direction-finding system.

Sanford was reading in his bunk early that April Fool’s morning in a building located on a terrace about 100 feet above the lighthouse.

“A severe earthquake was felt,” Sanford wrote. “The building creaked and groaned loudly. Objects were shaken from my locker shelf. Duration of the quake was approximately 30 to 35 seconds.”

[What killed the world’s giants?]

Knowing he was stationed on an island of restless mountains that include the steaming white pyramid of Shishaldin, Sanford looked inland for the glow of a possible eruption. He saw nothing but stars.

Then, 20 minutes after feeling the first earthquake, “a second severe quake was felt. This one was shorter in duration (than the first), but harder.”

Minutes later, a wave struck Sanford’s quarters.

“At 0218 a terrible roaring sound was heard followed almost immediately by a very heavy blow against the side of the building and about three inches of water appeared in the galley recreation hall and passageway … I went to the control room and … broadcast a priority message stating we had been struck by a tidal wave and might have to abandon the station.”

Sanford stepped outside. In the darkness, he picked his way to the edge of the hill above the lighthouse. He saw no lights below. The foghorn was silent.

“The Light Station had been completely destroyed.”

In the dawn of 7 a.m., Sanford and others descended the scarred hillside and tried to process the image of the naked shore. The ocean had calmed, looking no different than on any other day. The group searched the surrounding area, Sanford wrote.

“On top of a hill behind the Light Station we found a human foot, amputated at the ankle, some small bits of intestine which were apparently from a human being and what seemed to be a human knee cap.”

Three weeks later, while installing a temporary navigation light, a technician discovered another body. Others gathered and identified Paul Ness from his high cheekbones and goatee. Searchers then found the right thigh and foot of another man.

“These remains were gathered in old mail sacks and placed in a rough coffin. The body of Ness was placed in an individual coffin.”

Three days later, just before most of the men left Unimak on a Coast Guard cutter, the men buried their comrades. They were victims of a “near-field” local tsunami caused by underwater landslide, one of the greatest and most unpredictable threats to Alaska coastal villages during big earthquakes.

Alaskans have just minutes to react to these near-field tsunamis after feeling a large earthquake. Researchers at the Alaska Earthquake Center at the Geophysical Institute have mapped tsunami danger zones at https://earthquake.alaska.edu/tsunamis.

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. A version of this column appeared in 2015.